Trading strategies

Explore practical techniques to help you plan, analyse and improve your trades.

Our library of trading strategy articles is designed to help you strengthen your market approach. Discover how different strategies can be applied across asset classes, and how to adapt to changing market conditions.

.jpg)

Every trader has had that moment where a seemingly perfect trade goes astray.

You see a clean chart on the screen, showing a textbook candle pattern; it seems as though the market planets have aligned, and so you enthusiastically jump into your trade.

But before you even have time to indulge in a little self-praise at a job well done, the market does the opposite of what you expected, and your stop loss is triggered.

This common scenario, which we have all unfortunately experienced, raises the question: What separates these “almost” trades from the truly higher-probability setups?

The State of Alignment

A high-probability setup isn’t necessarily a single signal or chart pattern. It is the coming together of several factors in a way that can potentially increase the likelihood of a successful trade.

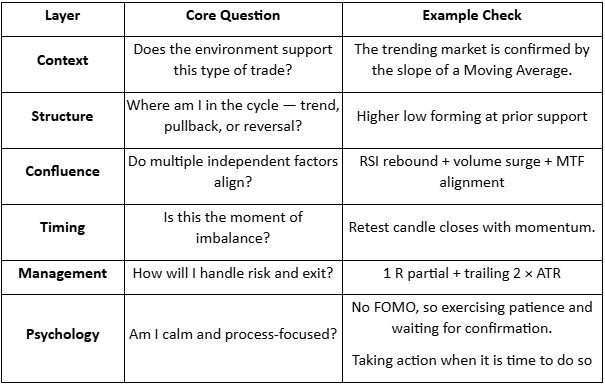

When combined, six interconnected layers can come together to form the full “anatomy” of a higher-probability trading setup:

- Context

- Structure

- Confluence

- Timing

- Management

- Psychology

When more of these factors are in place, the greater the (potential) probability your trade will behave as expected.

Market Context

When we explore market context, we are looking at the underlying background conditions that may help some trading ideas thrive, and contribute to others failing.

Regime Awareness

Every trading strategy you choose to create has a natural set of market circumstances that could be an optimum trading environment for that particular trading approach.

For example:

- Trending regimes may favour momentum or breakout setups.

- Ranging regimes may suit mean-reversion or bounce systems.

- High-volatility regimes create opportunity but demand wider stops and quicker management.

Investing time considering the underlying market regime may help avoid the temptation to force a trending system into a sideways market.

Simply looking at the slope of a 50-period moving average or the width of a Bollinger Band can suggest what type of market is currently in play.

Sentiment Alignment

If risk sentiment shifts towards a specific (or a group) of related assets, the technical picture is more likely to change to match that.

For example, if the USD index is broadly strengthening as an underlying move, then looking for long trades in EURUSD setups may end up fighting headwinds.

Setting yourself some simple rules can help, as trading against a potential tidal wave of opposite price change in a related asset is not usually a strong foundation on which to base a trading decision.

Key Reference Zones

Context also means the location of the current price relative to levels or previous landmarks.

Some examples include:

- Weekly highs/lows

- Prior session ranges, e.g. the Asian high and low as we move into the European session

- Major “round” psychological numbers (e.g., 1.10, 1000)

A long trading setup into these areas of market importance may result in an overhead resistance, or a short trade into a potential area of support may reduce the probability of a continuation of that price move before the trade even starts.

Market Structure

Structure is the visual rhythm of price that you may see on the chart. It involves the sequences of trader impulses and corrections that end up defining the overall direction and the likelihood of continuation:

- Uptrend: Higher highs (HH) and higher lows (HL)

- Downtrend: Lower highs (LH) and lower lows (LL)

- Transition: Break in structure often followed by a retest of previous levels.

A pullback in an uptrend followed by renewed buying pressure over a previous price swing high point may well constitute a higher-probability buy than a random candle pattern in the middle of nowhere.

Compression and Expansion

Markets move through cycles of energy build-up and release. It is a reflection of the repositioning of asset holdings, subtle institutional accumulation, or a response to new information, and may all result in different, albeit temporary, broad price scenarios.

- Compression: Evidenced by a tightening range, declining ATR, smaller candles, and so suggesting a period of indecision or exhaustion of a previous price move,

- Expansion: Evidenced by a sudden breakout, larger candle bodies, and a volume spike, is suggestive of a move that is now underway.

A breakout that clears a liquidity zone often runs further, as ‘trapped’ traders may further fuel the move as they scramble to reposition.

A setup aligned with such liquidity flows may carry a higher probability than one trading directly into it.

Confluence

Confluence is the art of layering independent evidence to create a whole story. Think of it as a type of “market forensics” — each piece of confirmation evidence may offer a “better hand’ or further positive alignment for your idea.

There are three noteworthy types of confluence:

- Technical Confluence – Multiple technical tools agree with your trading idea:

- Moving average alignment (e.g., 20 EMA above 50 EMA) for a long trade

- A Fibonacci retracement level is lining up with a previously identified support level.

- Momentum is increasing on indicators such as the MACD.

- Multi-Timeframe Confluence – Where a lower timeframe setup is consistent with a higher timeframe trend. If you have alignment of breakout evidence across multiple timeframes, any move will often be strengthened by different traders trading on different timeframes, all jumping into new trades together.

3. Volume Confluence – Any directional move, if supported by increasing volume, suggests higher levels of market participation. Whereas falling volume may be indicative of a lesser market enthusiasm for a particular price move.

Confluence is not about clutter on your chart. Adding indicators, e.g., three oscillators showing the same thing, may make your chart look like a work of art, but it offers little to your trading decision-making and may dilute action clarity.

Think of it this way: Confluence comes from having different dimensions of evidence and seeing them align. Price, time, momentum, and participation (which is evidenced by volume) can all contribute.

Timing & Execution

An alignment in context and structure can still fail to produce a desired outcome if your timing is not as it should be. Execution is where higher probability traders may separate themselves from hopeful ones.

Entry Timing

- Confirmation: Wait for the candle to close beyond the structure or level. Avoid the temptation to try to jump in early on a premature breakout wick before the candle is mature.

- Retests: If the price has retested and respected a breakout level, it may filter out some false breaks that we will often see.

- Then act: Be patient for the setup to complete. Talking yourself out of a trade for the sake of just one more candle” confirmation may, over time, erode potential as you are repeatedly late into trades.

Session & Liquidity Windows

Markets breathe differently throughout the day as one session rolls into another. Each session's characteristics may suit different strategies.

For example:

- London Open: Often has a volatility surge; Range breaks may work well.

- New York Overlap: Often, we will see some continuation or reversal of morning trends.

- Asian Session: A quieter session where mean-reversion or range trading approaches may do well

Trade Management

Managing the position well after entry can turn probability into realised profit, or if mismanaged, can result in losses compounding or giving back unrealised profit to the market.

Pre-defined Invalidation

Asking yourself before entry: “What would the market have to do to prove me wrong?” could be an approach worth trying.

This facilitates stops to be placed logically rather than emotionally. If a trade idea moves against your original thinking, based on a change to a state of unalignment, then considering exit would seem logical.

Scaling & Partial Exits

High-probability trade entries will still benefit from dynamic exit approaches that may involve partial position closes and adaptive trailing of your initial stop.

Trader Psychology

One of the most important and overlooked components of a higher-probability setup is you.

It is you who makes the choices to adopt these practices, and you who must battle the common trading “demons” of fear, impatience, and distorted expectation.

Let's be real, higher-probability trades are less common than many may lead you to believe.

Many traders destroy their potential to develop any trading edge by taking frequent low-probability setups out of a desire to be “in the market.”

It can take strength to be inactive for periods of time and exercise that patience for every box to be ticked in your plan before acting.

Measure “You” performance

Each trade you take becomes data and can provide invaluable feedback. You can only make a judgment of a planned strategy if you have followed it to the letter.

Discipline in execution can be your greatest ally or enemy in determining whether you ultimately achieve positive trading outcomes.

Bringing It All Together – The Setup Blueprint

Final Thoughts

Higher-probability setups are not found but are constructed methodically.

A trader who understands the “higher-probability anatomy” is less likely to chase trades or feel the need to always be in the market. They will see merit in ticking all the right boxes and then taking decisive action when it is time to do so.

It is now up to you to review what you have in place now, identify gaps that may exist, and commit to taking action!

The following EAs are examples of Expert Advisors rated on Trustpilot. They have been rated by traders in general, however, please understand that past performances are not indication of future success. Below is a list of EAs, which you can purchase online, however there are several free ones you can find on the market, these are labelled (f), please do your own research when choosing the right EA for your own trading style, objectives, and risk settings. 1000pip Climber – This EA has the highest rated metric on Trustpilot.

Apart from the added support that is on offer by the developers, this EA is specifically impressive given its high yield in both trending and range bound markets. Flex – Has been voted best EA on the market for an incredible 8 consecutive years! Flex requires a deposit of $3000 and works well in trending markets.

FXCharger – With a great yield of 77.3% and a high rating on Trustpilot, this EA opens trades every day and closes them at the right time, such that the trader earns a profit. FXCharger requires a deposit of $1000. Fortnite – Another customisable EA that allows the user to change the settings according to the trading style they want.

Is yield ranks around the 135%, it requires a deposit of $500. Alfa Scalper – Using a scalping method to get trading opportunities this EA yields sits at 49.36% and has a rating of 8.57. Its one of the easiest EAs to use and requires a deposit of $100.

Forex Gump – It’s probably one of the most rated EAs by traders on the market, it has a rating of 8.52 and a yield of 2200%. It utilizes daily trading and scalping to make trading decisions. This one requires a small deposit of $40.

Trade Manager – With a 65.39% yield, you can create your own strategies and set your own parameters for the best results. A deposit of $100 is required. Forex Diamond – Has a yield of 63.39%.

This EA uses trend and countertrend strategies to make trading decisions, is fast, safe, and precise. Requires a deposit of $1000. Below is a list of free experts’ advisors which you can look up with the power of the internet: Trader New (f).

Daydream01 (f). Calypso (f). Day Profit SE (f).

Breakout11 (f). Euro FX2 (f) Channels (f). As a trader it is important to know what type of trading you would like to do, this means what types of strategy, which markets and if you would benefit from the use of an EA or if you would prefer to trade manually.

If you are thinking that having access to an EA might benefit your trading activity, then there are many available on the MQL5 commuminty. If you are interested in automating your own strategy, then there are companies like TradeView that help traders to automate and create their own Expert Advisor without coding experience. GO Markets also provides access to their TradeView X platform via the client portal with a monthly subscription at a reduced cost other than directly with them.

By having an account with GO Markets you will also have access to our Metatrader 4 and 5 trading platform and a VPS (needed for EA traders). Please visit us here to get started or call us directly and speak to one of our account managers on 03 8566 7680. Sources: tradersunion.com.

Trading FOREX, equities, commodities, and any other asset can be an emotional rollercoaster. With so many different emotions and external factors difficulties impacting a trade, it is crucial that before any trade is executed a trading plan is produced to minimise the impact of the ‘noise’. Generating the Idea The first step to any plan is to generate a trading idea.

Trade ideas, come from one of three sources. A fundamental source, a technical source, or a mix of both. What does this mean exactly?

Well, when generating ideas from a fundamental perspective, a trader can generate idea based on economic events, monetary policy from a Central bank or company relevant information just to name a few. From a technical perspective, a trader may find that an asset is trading near a potential support or resistance level or developing into a breakout pattern. Alternatively, the price may have touched an important moving average which indicates it may be ready to trade.

Traders can also put these ideas together to come up with even more robust trading ideas. Background economic factors and sector analysis Before entering a trade, a good trader should have at the very least a rudimentary understanding of the relevant sector or economic factors that may influence the trade. For example, a trader decides to trade the AUDUSD currency pair.

The trader has seen that the price is approaching a short-term support point and decides to buy the pair expecting the price to bounce of the level. However, the trader is not aware that the Federal Reserve has just increased interest rates which has increased the value of the USD. Consequently, the price goes against the trader.

Technical breakdown Prior to entering any trade, the trader should analyse the price chart and set up relevant support and resistance levels. This allows the trader to have a clear idea of key supply and demand zones for the asset before the emotions of the actual trade become prevalent. To effectively go about this step, support and resistance levels can be analysed on multiple time frames to gain an even greater edge. [caption id="attachment_272243" align="alignnone" width="2560"] Business Team Investment Entrepreneur Trading discussing and analysis graph stock market trading,stock chart concept[/caption] Entry condition Having a trade idea is one aspect however having a clear entry criterion will help reduce the impact of emotion when watching the trade unfold.

Some examples of potential entries conditions can be related to a break and retest of a certain level for an entry or waiting for a specific candlestick pattern. Furthermore, an entry may also be defined by a disproportionate increase in volume supporting a breakout. Exit Conditions Like determining entry conditions having pre planned exit points can improve the management of emotions during also trade whilst also enhancing risk management.

Setting take profit targets/stop loss areas will help ensure that a trade is well structured even before initiating the trade. Having pre-determined exit points can also help determine if a trade is worth entering in the first place as it allows for a determination of the potential risk reward before execution. Risk management No matter whether the trade is a scalp, swing trade or longer-term investment, each should have clear risk management guidelines.

Good risk management involves the use of stop losses and correct sizing of a trade. One method that can be effective is to have a maximum amount of the total account that you are willing to lose per trade. This could be a percentage figure or a fixed amount.

For example, if the total account size is $10,000 and you decide that the maximum loss per trade is 1%. This means that the maximum loss per trade would be $100. The next step is to then set stop loss.

The stop loss in many cases should be independent of the actual maximum risk amount. The stop loss level should be calculated before the sizing. Once the stop loss is set the size of the trade can be determined.

Risk management is perhaps the most crucial element of the trading plan because minimising losses is crucial to any long-term success in trading. Whilst having a clear trading plan will not guarantee success it will help remove many behavioral biases that can impact on a trade.

Is it time to Capitalise on Short Squeezes ? Short Squeezes are one of the interesting price action patterns that can occur in the market. They can provide It can provide explosive momentum trading opportunities that can go on for days.

They can provide trading opportunities for scalpers, intraday, and swing traders. What actually is a short squeeze and why do they occur? To understand a short squeeze it is important to go back to the basics of trading and understand what an actual short is and why market participants go short on a product.

What is a short? A short is a position that a market participant takes when they expect the price of a market product to go down. This can include but is not excluded too, Securities, Commodities and Forex.

A trader may take a short position because they believe a company is overvalued, a currency will go down in value due to economic factors, to hedge or for a number of other reasons. Short positions can be taken in a range of ways, however, the most common method for shorting a CFD is quite simple. It involves borrowing units to sell with the short holder having to buy-back the units at a lower price and pocketing the difference.

Example A trader believes that company ABC is overvalued at $1.00 and decides to borrow 100 CFD units of ABC to short at $1.00 per CFD with a total value of $100. The price then falls to $0.50. The trader closes their position and buys back the CFDs at $50.

They are then able to pocket the difference of $50.00. The mechanics of a short squeeze. Due to the nature of a short position which requires a buying back of the stock to both close the position and lock in profit a trader will inevitably have to buy-back or close their position at some point.

This subsequently drives up the price. Most of the time in a trending market this process works without any issues. However, if the price stops falling and consolidates or to a stage where the market starts to see value in the price again, large short holders may decide to close out their position.

If big positions or institutions close all at once it can create an avalanche effect. Indicators of a short squeeze A stock, currency, or commodity that is highly shorted or is overextended to the sell side is often ripe for a squeeze. In addition, if the underlying asset is getting closer to an area of support or resistance it may show that the selling has dried up.

Shorters may then need to close their positions soon otherwise they risk holding losing positions If a stock is bottoming or basing it may indicate that buyers are beginning to take control of the price again. This shows that the asset has reached a point where it really can’t fall any further in price because buyers see too much value. A shift in the relative volume can indicate that either a big position is closing or buyers have found an area of value and that the price might be ready to reverse.

The large volume can also indicate that an institution is playing an active role in the price. It is usually good practice to follow where the big money is when trading. Squeezing in the current market A short squeeze can represent a great opportunity to profit for traders.

They can often be explosive moves and last for days. This means that whether you are a swing trader, day trader, or a scalper anyone can capitalise on a squeeze. In addition, with the current state of the market having one of its worst first half of the years in history, with bearish sentiment being very high.

The Nasdaq in particular and growth stocks in particular have seen their value smashed. As big short positions have been taken at some stage they will have to be closed and if the market can rally, then this phenomenon may become more regular. For instance the company ZIP a strong player in the Buy Now Player Sector had seen its share priced reduced to a fraction of its peak prior to just a few weeks ago.

However as seen in the chart below, a shift in volume was the first signal that the stock was about squeeze and shift strongly to the upside. In this instance, ZIP on the weekly chart saw a massive jump in volume, followed by an even larger jump in volume the following week. Importantly ZIP, according to (Shortman.com.au) had a short % of 7.34 on July 1 2022, prior to the breakout.

Looking at the daily chart underneath, the sheer volume of buying continued to get larger and larger which is indictive of a short squeeze as large positions began to close. The subsequent price action provided great consistent buying opportunities for traders.

Market response to any specific economic data release is far from standard even if actual numbers differ greatly from consensus expectations. Rather the market response is based on context of the current economic situation. This week’s non-farm payrolls, being one of the major data points in the month, is a great case in point.

There are many factors and of course the key one for you as an individual trader is your chosen vehicle you are trading (and of course direction i.e. long or short for open positions). The context of today’s impending non-farm payrolls from a market perspective is interest rate expectations going forward. This week the Fed gave the market the expected.25% cut that was already priced into currency, bond and equity market pricing.

The market response however, as this was already priced in, was as a result of the accompanying statement which was not as dovish as perhaps anticipated and a reduction in expectations of a further imminent cut. From an equity market point of view the result, despite the interest rate cut, was to sell off, whereas from the USD perspective this lessening expectation of further rate cuts was bullish. Perhaps this could be viewed as contrary to what the textbooks would suggest is a standard response.

So, onto todays non-farm payrolls (NFP) figure… Logic would suggest that a strong number is good news for the economy, and so should be positive for equities and perhaps bearish for USD. However, as this may be a critical number in the Feds decision making re. interest rate decisions, a strong NFP is likely to have the opposite effect. A weaker number is likely to be perceived as potentially contributory to thinking that another rate cut may be prudent sooner and so despite on the surface being “bad news”, it would not be surprising to see equities stronger and USD weaker.

It remains to be seen of course what the number is and the actual response but is perhaps a lesson in seeing new market information within the potential context of the current economic circumstances and of course incorporate this in your risk assessment and trading decision making.

Many traders utilise shares or options amongst their investment strategies either for income or capital growth. One key factor that such traders may consider in their choice of specific markets to trade is liquidity, with a higher trading volume impacting positively on the ability to get in and out of trades at a fair price. Others may find the choice to trade specific companies or sectors not as well represented in their local market.

For many therefore, the breadth of choice and liquidity may make this market the preferred market to trade. Like any type of trading, sustainable results require a depth of knowledge and commitment to trading an individual tried and tested system. This system should include in depth reference to risk management throughout.

However, due to the choice of market, a trader can make regular profit and yet lose this (and potentially more) through the currency risks associated with trading in US dollars rather than, for example, their base currency of Australian dollars or GB pounds. Holding a significant position in US shares or options means that many traders have exposure to positions in tens of thousands in USD. So what is the currency risk?

The reality is that profits can be ‘used up’, or losses can be compounded, by adverse currency movements. The reason for this is simple. Let’s assume that your currency is AUD and it is transferred into USD for trading purposes.

The exchange value when converted back to the original currency at some time in the future will be dependent not only on trading results but on the movement of AUD versus USD. While your money is in your account in USD, weakness in AUD will mean a greater worth in AUD when converted back, whereas a lesser conversion worth will result if there is AUD strength while your money is sitting is USD. Let’s give an example...

See below a daily chart of AUD/USD for the last 3 years. Note the price from the end of January 2018 at a level of 0.8134. The price at Nov 2019 was at 0.6776 so a difference of 0.1358 So, an investment to fund a trading account of AUD$30,000 would have equalled an original USD value of $24,402.

With the movement in the currency alone over this period (assuming no movement in share price) the value of the account when transferred back into AUD would have risen to $36,007.59 or in other words a 20.03% increase. So, in this case the underlying currency movement was of benefit. However, if this positive currency outcome is the case when there is USD strength (when your trading capital is in USD), with the same AUDUSD currency movement in the other direction, the loss could be 20.03%.

This would mean that you would have had to profit by this 20.03% in your trades simply to breakeven. This WAS the case if you look at a chart from the beginning of Jan 2016 to Aug 2017. More than this of course, if you have lost $6007.59 on a similar price move in the other direction, broke even on your trades during that period, so your equivalent AUD value is $23,992.41, your trading return would have to be now 25% profit to recover the original capital level simple because of currency movement.

Bear in mind, of course we have chosen only a $30,000 example, some of you may have considerably more than this in the market (and so considerably more currency risk) than the example we have given. Risk management of your hedge Although you are entering a low margin requirement Forex position due to the leverage associated with Forex, we cannot understate the importance of a full understanding of the implications of this. Should the AUD move lower still (as we explained above in looking at what has happened since January 2018), the value of your hedge may move significantly.

If we look at using the analogy of an insurance policy in trying to explain the concept, the maximum risk is the initial “premium” paid in this case. However, with any Forex position there is obviously the risk of losing more than your original investment. Additionally, you are trading your shares/options in a different account and hence there must be the ability to money manage between the two accounts.

Our team can guide you further on these important issues. One last thing… Although we cannot advise when it is right for you, if at all, to put in a currency hedge, it is worthwhile raising the question about what the current AUDUSD chart is telling you now technically. Additionally, with the potential for further US rate cuts, and if you believe there will be some resolution to trade tariff wars between the US and China, both events have the potential to strengthen AUD (and so weaken your USD capital).

If invested in USD based trading for some time you have benefitted, logically, it is not unreasonable to consider whether it is worth ‘locking’ some of this in. So, what can you do? Your choices are twofold. 1.

Allow your invested trading capital to be subjected to the risks associated with underlying currency movements or, 2. Hedge the currency risks with a non-expiring Forex position. If option “2” looks attractive, the reality is you can: • Mitigate the risk through consideration of a Forex hedge. • Attempt to optimise your hedge by timing its placement and exit i.e. use technical landmarks, to decide when to get in and out of a hedge. (Please note: a hedge is for insurance purpose and so although there may be merit in timing entry and exit, we are not suggesting you trade in and out of a hedge on a regular basis).

Learn how to reduce the risk We are happy not only to show you how but guide you step by step in how to set this up. There are a couple of practical issues you would need to have in place to manage this well but again we can go through these to enable you to make the right decision for you. If you think this might be for you, then simply connect with us at [email protected] and we will arrange for one of our account team to discuss a currency hedge that may be a fit for you.

Irrespective of what vehicle you are choosing to trade (Forex, CFDs, share CFDs ), position sizing is a crucial part of your trading risk management. It is position sizing, along with effective exit strategies, that have an undoubted major impact on your trading results both now and going forward. At a basic level, the following are part of a position sizing system: a.

Identify a tolerable risk level per trade based on your account size (often 1-3%) meaning you aim to keep any loss sustained within this tolerable limit. b. Using any stop level for specific trades and your tolerable limit to work out how many lots/contacts you can enter to achieve this goal. c. Ensuring you are not inadvertently over-positioning in one market idea (e.g. broad-based USD strength or weakness, by entering multiple trades across currency pairs/ commodity CFDs that will multiply the impact of USD movement).

But what then? How do we explore refining our position sizing to potential optimise results? Here are two initial ideas for potential testing… Idea 1 – Position sizing according to volatility When exploring using volatility for any trading decision it is not just the level but potentially, more importantly, the direction of the volatility i.e. increasing/decreasing.

Volatility is often seen as a reflection of market certainty but perhaps consider volatility as a measure of the likelihood that an asset e.g. Fx pair, is more likely to move away from its current position (and that can be either positively or negatively of course). Logically, therefore, increasing volatility in either direction could represent an increase in risk (and of course visa versa).

Consequently, it is not unreasonable to consider altering your tolerable risk level according to this. So, for example, if your standard is 2% of account capital on any one trade, if you were to implement this as an idea, increasing volatility could mean a decrease in risk level to 1% and decrease to 3%. The challenge, of course, is to determine a method through which you can determine this change.

The ATR is a volatility measure commonly used and would be a potential tool that can assist. Of course, the other aspect is to choose the timeframe to measure this variable. Logically, the shortest timeframe should be the timeframe you are trading but there may be wisdom in looking at longer-term timeframes also.

Idea 2 – Ensure that trail stops account for your tolerable risk level. Arguably a common mistake made by many traders is to view trades on their P/L and make decisions on the fact they are “up” on the deal and as long as the trade is closed before getting back to breakeven then they have a win. An alternative and logically an advanced approach is your net worth in the market is where it is right NOW and hence any pullback in any position is a “loss” from your current place.

This is the rationale behind trailing a stop in an attempt to still have access to the further upside (“letting your profits run”) whilst capping any pullback to a new an improved level to that of your initial stop. There are many ways of trailing a stop e.g. retracement, price/MA cross but again would it not make sense to use your tolerable risk level as part of your trail stop equation. So lets see, for example, use an account size of $10,000 and you are trading a 2% maximum risk level to set your initial stop.

This means that your contract/lot size is based on your technical stop and $200. You have a position that is now up to $350 if you were to adopt this approach when you trail your stop you should ensure that it is placed at a level that would mean that the worst scenario would be that you would close the position at $150 profit. There are of course other advanced position sizing techniques you could test which will be the topic of an upcoming Inner Circle session.

Make sure that you are part of this through registering for these sessions so you can jump on board with this advanced trading education group to access the topics applicable to your trading development. In the meantime, we would be delighted, as always, to hear from you, so if you are using an advanced position sizing technique it would be great to hear from you at [email protected]