Noticias del mercado & perspectivas

Anticípate a los mercados con perspectivas de expertos, noticias y análisis técnico para guiar tus decisiones de trading.

Los datos de inflación de Estados Unidos del miércoles son la pieza central de la semana, pero con el petróleo acercándose a máximos de siete meses, el sentimiento de Bitcoin (BTC) cambiando y el dólar australiano en máximos de tres años, los comerciantes tienen mucho que navegar en la próxima semana.

Datos rápidos

- La tasa de inflación de Estados Unidos (febrero) es el evento binario clave para la fijación de precios de reducción de tasas y la dirección de la renta variable.

- El crudo Brent cotiza alrededor de US$82—84/BBL, cerca de máximos de siete meses, con una prima de riesgo geopolítico de 4 a 10 dólares gracias a las tensiones entre Irán y Ormuz.

- Bitcoin cotiza por encima de los 70.000 dólares al 6 de marzo, un posible cambio de tendencia si se mantiene a lo largo de la semana.

Estados Unidos: la inflación en foco

La lectura de inflación estadounidense del mes pasado mostró que los precios subieron 2.4% interanual, aún muy por encima de la meta de 2% de la Fed.

La tasa de inflación de febrero, que vence el miércoles, será examinada en busca de señales de que la traspaso de las tarifas o el aumento de los costos de la energía están haciendo que los precios vuelvan a subir, o si la lenta bajada sigue intacta.

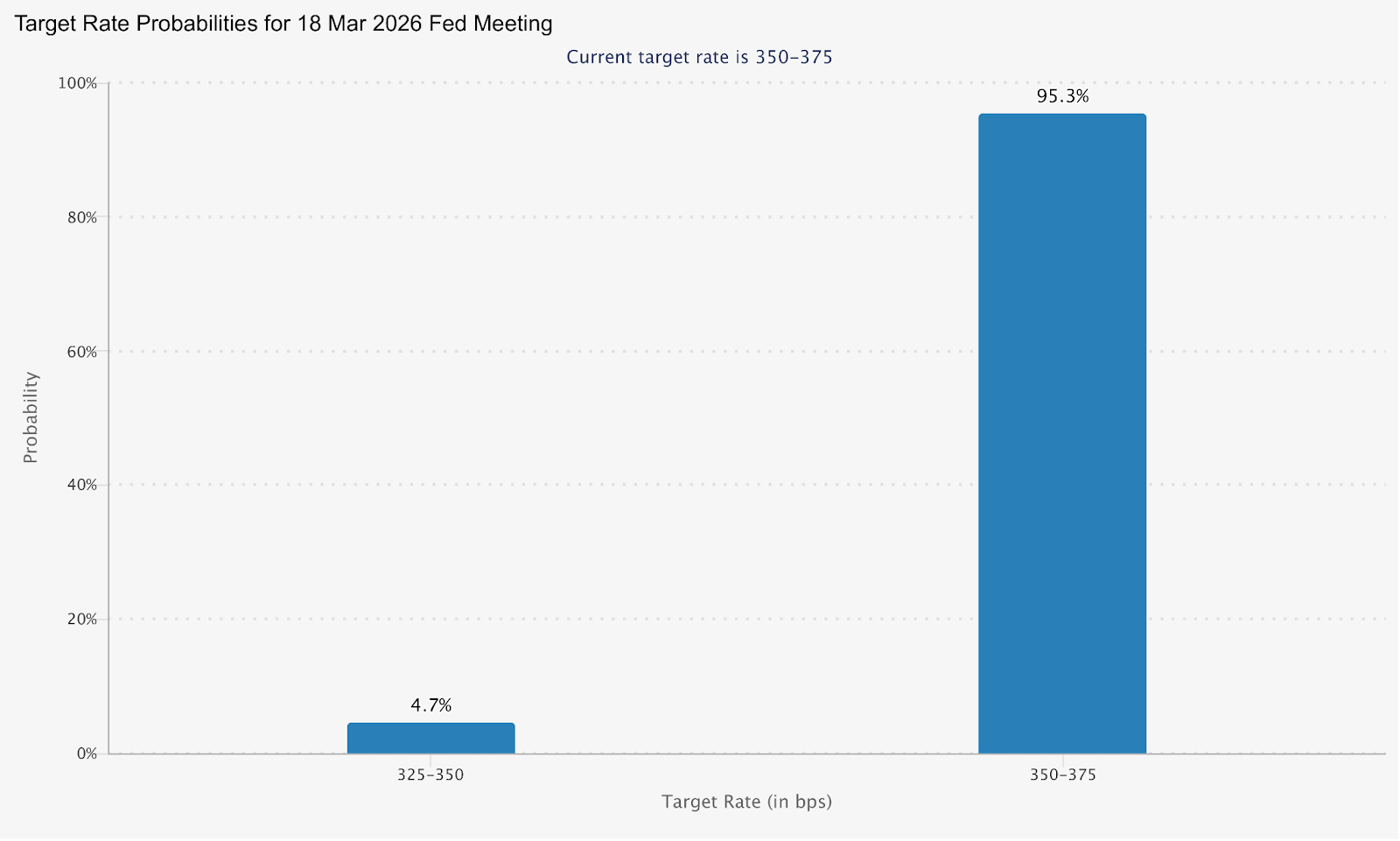

La reunión del FOMC de marzo del 17 al 18 de marzo ahora tiene un precio de solo 4.7% de probabilidad de un recorte. Una impresión de inflación más alta de lo esperado esta semana podría potencialmente empujar aún más las expectativas de recorte de tasas.

Una lectura más suave abre la puerta a una nueva reducción de precios y un posible alivio en los activos de riesgo.

Fechas clave

- Tasa de inflación de Estados Unidos (IPC de febrero): Miércoles 11 de marzo, 12:30 h (AEDT)

Monitorear

- La divergencia de inflación básica frente a la general como evidencia de traspaso arancelario en los precios de los bienes.

- Sensibilidad de rendimiento de tesorería a 2 y 10 años a la impresión.

- Dirección del USD y retarificación de FedWatch antes de la decisión del FOMC del 18 de marzo.

Aceite: elevado y sensible a los eventos

Actualmente, el Brent cotiza alrededor de US$83—85 por barril, con un rango de 52 semanas que abarca US$58,40 a US$85,12, lo que refleja el dramático movimiento desencadenado por el conflicto de Oriente Medio.

Analistas estiman que la prima de riesgo geopolítico ya horneada al petróleo en 4 a 10 dólares por barril, y los pronósticos promedio del Brent 2026 se han elevado a 63,85 dólares por bbl, frente a los 62,02 dólares de enero.

El Perspectiva Energética a Corto Plazo de la EIA pronostica que el Brent promediará $58/bbl en 2026, muy por debajo del precio spot actual.

La brecha entre el spot y la línea base del pronóstico podría ser un marco útil para los comerciantes esta semana: cualquier señal de desescalada de Oriente Medio podría cerrar rápidamente esa brecha.

Monitorear

- Desarrollos del Estrecho de Ormuz y cualquier señal diplomática de las conversaciones nucleares de Irán.

- Datos de inventario de petróleo semanal de EIA.

- El derribación del petróleo a las expectativas de inflación y si cambia la postura del banco central.

- Desempeño de la renta variable del sector energético en relación con el mercado en general.

Bitcoin: vigilancia del sentimiento

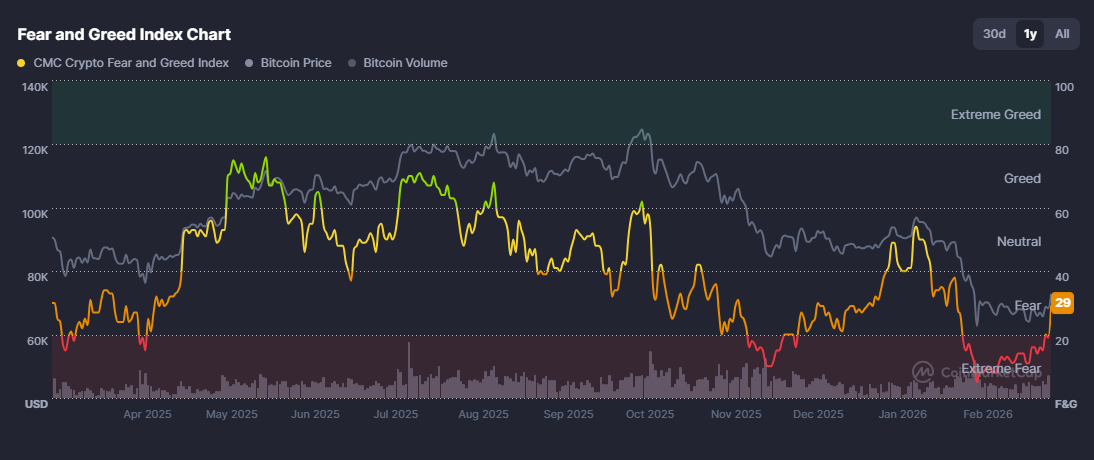

BTC ha estado intentando estabilizarse después de una brutal corrección del 53% en las últimas 17 semanas, alimentada por la escalada de tensiones geopolíticas y las renovadas preocupaciones arancelarias.

No obstante, ayer se vio un salto de 8% por encima de los 72,000 dólares, y el cripto “índice de miedo y codicia” saltó a 29 (miedo), arriba desde debajo de 20 (miedo extremo), donde lleva más de un mes sentado, lo que indica un posible cambio de sentimiento.

Una impresión de inflación estadounidense más fresca de lo esperado el miércoles podría proporcionar más combustible para la ruptura; una impresión caliente corre el riesgo de que BTC vuelva a estar por debajo del nivel de US$70,000 que acaba de recuperar.

Monitorear

- Inflación impresión reacción el miércoles como el macrocatalizador primario de la mudanza.

- Cualquier rotación a altcoins siguiendo la fuerza de BTC.

- Datos de entrada/salida de ETF como confirmación de participación institucional.

AUD/USD: El RBA de Hawkish se encuentra con vientos cruzados geopolíticos

El australiano cotiza cerca de máximos de más de tres años y se dirige a su cuarta ganancia mensual consecutiva, con un aumento de más del 6% en lo que va de año, lo que la convierte en la moneda del G10 de mejor desempeño en 2026.

El impulsor es una clara divergencia política. La gobernadora del RBA, Michele Bullock, señaló que la reunión de política de marzo está “viva” para un posible aumento de tasas, y advirtió que un choque en el precio del petróleo por las tensiones en Irán podría reavivar las presiones inflacionarias internas.

Los precios de mercado ahora sugieren alrededor de un 28% de posibilidades de una subida de 25 pb en la próxima reunión, mientras que la fijación de precios por completo se ajustará hasta mayo, y alrededor de un 75% de probabilidad de otro aumento a 4.35% para fin de año.

Esta lectura tensa, puesta en contra de una Fed en espera y que enfrenta una presión política dótica, crea un potencial viento de cola estructural para el australiano.

Monitorear

- Reacción del AUD/USD al dato de inflación estadounidense del miércoles.

- Probabilidad de alza de tasa del RBA reajuste de precios a lo largo de la semana.

- El mineral de hierro y los precios de las materias primas como impulsores secundarios del AUD.

- China demanda señales, dada la exposición exportadora de Australia.

Recent US figures have seen a rout in treasury yields with the flagship 10-year now yielding 4.435% after starting November at 16-year highs north of 5% and in a seemingly unstoppable uptrend. A cooler CPI and PPI showing inflation is decelerating at a faster pace than the market anticipated, along with weaker employment and industrial production figures have traders re-adjusting for a less hawkish Fed and bringing their timing forward for the pricing in of rate cuts. Why this is important to serious FX traders is because rates and FX have a high correlation, even more in the post pandemic period of cuts, hikes and peak rates and maybe cuts again, big FX traders look for yield and that can be used as important information for smaller players to position themselves to take advantage of that.

An example of this relationship can be seen on the weekly chart of the US Dollar index below. The US dollar Index has fallen 2.5% so far in November, a move first started with the big miss in NFP which saw support at the 23.6 Fib level broken, then accelerating this week on a Cooler CPI which saw it take out the 38.2 Fib level support which the price is currently hovering around at 104.41. This along with the situation in yields will be the level to watch in the short term, if yield and dollar bulls take charge a break and support hold could see USDollar first test the lower trend line resistance, with the next stop from a technical point of view being the 23.6 Fib level resistance at 105.545.

To the downside if yields continue their fall the next technical support will be the 50% fib level, paired with the 200-day moving average. Next week there are a few important data points with FOMC minutes, consumer sentiment and manufacturing figures all scheduled. For FX traders they will be worth watching for any further clues as to yields and where traders think they will go as they work to front run the Fed.

Australian employment change for October was released today and showed a decent beat of +55k jobs added vs an expected 22.8k while the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.7% in line with expectation. AUDUSD reaction was muted, with markets still convinced that we have seen the peak in the RBA rate cycle with futures barely moving the needle on rate hike odds for the RBA December meeting. We did see a small pike higher of around 12 pips on the release, but it seems the resistance above 0.6500 for this pair is going to be tough to crack and the cross rate quickly retraced to a level below when the reading was released.

Looking at the AUDUSD 4-hour chart a double top of testing the major resistance level is forming with both tops entering the extreme RSI overbought level. A repeat of the AUDUSD sell-off back to the range mid-price of 0.6400 is looking a possibility for this pair unless we see another sell-off of the US Dollar. The sole tier 1 news release out of the US for the remainder of this week is weekly unemployment claims, so that will be the one to watch.

If you're an existing GO Markets client, simply get in touch with a member of our Support Team and we'll help you get set up. How it works: GO Markets offers complimentary monthly VPS subscription to clients who have completed a minimum trade volume of US $1 Mil per calendar month (approximately 5 round turn FX lots). A service fee starting from US$10 (or Account Currency Equivalent) per month will be charged to your trading account if the monthly trade volume is not met.

If you do not meet the above criteria, you can still subscribe. However, a monthly fee of US$30 (or Account Currency Equivalent) will be charged to your trading account. Your VPS subscription will be terminated when you close your Trading Account with GO Markets or the Equity Balance of your Trading Account falls below A$30 (or Account Currency Equivalent.) You can also terminate your VPS subscription at any given time by contacting our Support Team.

Terms and Conditions: Trading Volumes are calculated for a calendar month, from the Sydney open on the first trading day of the month, to the New York close on the last trading day of the month. Qualifying trades include any FX, Metals, Indices and Commodities volume. The VPS is provided by a specialised third-party, and as such, GO Markets does not guarantee the uptime or performance of the VPS service.

GO Markets accepts no liability for any adverse effects to our Trading Account following the withdrawal of the monthly fee, if required. Offers cannot be used in conjunction with any other promotional offer. All GO Markets offers are only available in accordance with applicable law.

GO Markets offers are not designed to alter or modify an individual’s risk preference or encourage individuals to trade in a manner inconsistent with their own trading strategies. Traders should ensure that they operate their trading account in a manner consistent with their trading comfort level. It is at GO Markets sole discretion to cease any of our promotional offers at any point in time.

It is at GO Markets sole discretion to exclude you from the complimentary VPS subscription if we believe you have instigated any fraudulent activities or your actions are to be found in violation of our terms and conditions or the terms and conditions of the specific offer. GO Markets reserves the right to decline any application or indication to participate in any promotion at its sole discretion, without the need to provide any justification or explain the reasons for such a decline. VPS is available for both MT4 and MT5 MetaTrader software.

USD was mildly bid on Monday ahead of a very busy calendar starting with US CPI later today. The US Dollar Index (DXY) rose to a high of 104.26, testing its trendline resistance before paring back to finish the session modestly in the green. DXY continuing to trade in the tight range between its 200-Day MA to the downside and resistance at around 104.25 to the upside.

USD traders have a busy week ahead, along with CPI today, PPI and the FOMC rate announcement are ahead tomorrow. The Japanese Yen dumped after a Bloomberg report citing BoJ sources that said the BoJ sees little need to end negative rates in their December meeting. This saw rates markets rapidly reprice what was a 20% chance of a rate hike, down to just 5%.

This translated to a short squeeze on USDJPY as carry traders flooded back in and saw the pair rally to a high of 146.46. Gold saw another large decline, with XAUUSD dropping almost $30 USD an ounce, breaking through the psychological 2000 level and hitting 3-week lows. XAUUSD now sitting on its 50% Fib retracement support, with the next support lower around the 1950-52 level at the 200-day MA and 61.8 fib level.

Ahead today, the real data starts, headlining will be US CPI where the Y/Y figure is expected to moderate to 3.1% vs 3.2% previous.

Target Corporation (NYSE: TGT) released Q3 financial results before the market open in the US on Wednesday. The US retail giant beat both revenue and earnings per share (EPS) estimates for the previous quarter, sending the stock higher. Company overview Founded: June 24, 1902 Headquarters: Target Plaza Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States Number of employees: 440,000 (2023) Industry: Retail Key people: Brian Cornell (Chairman & CEO) The results Target reported revenue of $25.398 billion for Q3 (down by 4.2% from the same period in 2022) vs. $25.285 billion estimate, according to TradingView.

EPS reported at $2.10 per share (up by 35.9% year-over-year), exceeding analyst estimate of $1.474 per share. CEO commentary "In the third quarter, our team continued to successfully navigate our business through a very challenging external environment. While third quarter sales were consistent with our expectations, earnings per share came in far ahead of our forecast.

This profit performance benefited from our team's commitment to efficiency and disciplined inventory management, and I'd like to thank them for their tireless efforts. Looking ahead, we're continuing to make investments throughout our business -- in our assortment, our team and the services we offer -- to provide the newness, affordability and convenience our guests want during the holiday season and beyond," company CEO, Brian Cornell commented on the latest results and future plans. The stock was up by over 16% after posting better-than-expected results.

Shares were trading at around $129.55 – the highest level since 18/8/2023. Stock performance 1 month: +17.13% 3 months: +0.26% Year-to-date: -13.39% 1 year: -16.97% Target price targets Jefferies: $135 Telsey Advisory Group: $145 Tigress Financial: $180 Evercore ISI Group: $130 B of A Securities: $135 Truist Securities: $116 Stifel: $130 HSBC: $140 Morgan Stanley: $140 Target Corporation is the 270th largest company in the world with a market cap of $59.61 billion, according to CompaniesMarketCap. You can trade Target Corporation (NYSE: TGT) and many other stocks from the NYSE, NASDAQ, HKEX, ASX, LSE and DE with GO Markets as a Share CFD.

GO Markets now offers pre-market and after-market trading on popular US Share CFDs. Trade the pre-market session: 4:00am to 9:30am, normal session, and after-market session: 4:00pm to 8:00pm, Eastern Standard Time. Why trade during extended hours?

Volatility never sleeps. Trade over earnings releases as they happen outside of main trading hours Reduce your risk and hedge your existing positions ahead of a new trading day Extended trading hours on popular US stocks means extended opportunities Sources: Target Corporation, TradingView, MarketWatch, MetaTrader 5, CompaniesMarketCap, Wikipedia

Home Depot Inc. (NYSE: HD) released its latest financial results before the opening bell in the US on Tuesday, beating analyst estimates for the third quarter. Company overview Founded: February 6, 1978 Headquarters: Atlanta, Georgia, United States Number of employees: 471,600 (2023) Industry: Retail Key people: Ted Decker (President & CEO), Craig Menear (Chairman) The results The US retailer reported revenue of $37.71 billion (down by 3% year-over-year) for Q3 vs. $37.591 billion expected. Earnings per share (EPS) reported at $3.81 per share (down by 10.14% year-over-year), above $3.755 per share estimate.

CEO commentary "Our quarterly performance was in line with our expectations," Ted Decker, CEO of Home Depot said in a press release to investors. "Similar to the second quarter, we saw continued customer engagement with smaller projects, and experienced pressure in certain big-ticket, discretionary categories. We remain very excited about our strategic initiatives and are committed to investing in the business to deliver the best interconnected shopping experience, capture wallet share with the Pro, and grow our store footprint. In addition, our associates did an outstanding job delivering value and service for our customers throughout the quarter and I would like to thank them for their dedication and hard work," Decker added.

Shares of Home Depot rose by over 6% on Tuesday after the latest earnings results. The stock was trading at $307.06 a share – the highest level since 25/9/2023. Stock performance 1 month: +3.58% 3 months: -7.71% Year-to-date: -2.95% 1 year: -1.73% Home Depot price targets Stifel: $306 RBC Capital: $303 Truist Securities: $341 HSBC: $365 Jefferies: $384 Morgan Stanley: $350 Wedbush: $350 Wells Fargo: $360 Barclays: $333 JP Morgan: $335 Goldman Sachs: $350 Home Depot Inc. is the 26th largest company in the world with a market cap of $307 billion, according to CompaniesMarketCap.

You can trade Home Depot Inc. (NYSE: HD) and many other stocks from the NYSE, NASDAQ, HKEX, ASX, LSE and DE with GO Markets as a Share CFD. GO Markets now offers pre-market and after-market trading on popular US Share CFDs. Trade the pre-market session: 4:00am to 9:30am, normal session, and after-market session: 4:00pm to 8:00pm, Eastern Standard Time.

Why trade during extended hours? Volatility never sleeps. Trade over earnings releases as they happen outside of main trading hours Reduce your risk and hedge your existing positions ahead of a new trading day Extended trading hours on popular US stocks means extended opportunities Sources: Home Depot Inc., TradingView, MarketWatch, CompaniesMarketCap, Wikipedia, Benzinga, Stock Analysis