Estrategias de trading para respaldar tu toma de decisiones

Explora técnicas prácticas para ayudarte a planificar, analizar y mejorar tus operaciones.

.jpg)

Every trader has had that moment where a seemingly perfect trade goes astray.

You see a clean chart on the screen, showing a textbook candle pattern; it seems as though the market planets have aligned, and so you enthusiastically jump into your trade.

But before you even have time to indulge in a little self-praise at a job well done, the market does the opposite of what you expected, and your stop loss is triggered.

This common scenario, which we have all unfortunately experienced, raises the question: What separates these “almost” trades from the truly higher-probability setups?

The State of Alignment

A high-probability setup isn’t necessarily a single signal or chart pattern. It is the coming together of several factors in a way that can potentially increase the likelihood of a successful trade.

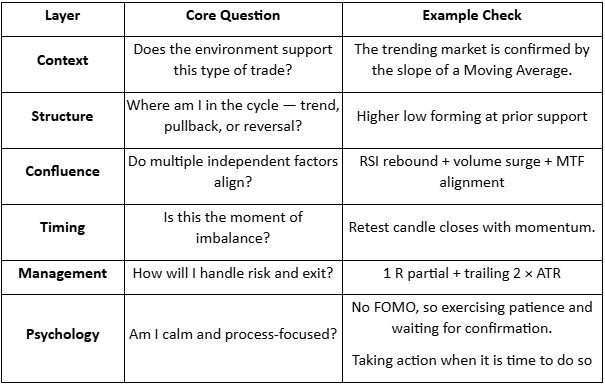

When combined, six interconnected layers can come together to form the full “anatomy” of a higher-probability trading setup:

- Context

- Structure

- Confluence

- Timing

- Management

- Psychology

When more of these factors are in place, the greater the (potential) probability your trade will behave as expected.

Market Context

When we explore market context, we are looking at the underlying background conditions that may help some trading ideas thrive, and contribute to others failing.

Regime Awareness

Every trading strategy you choose to create has a natural set of market circumstances that could be an optimum trading environment for that particular trading approach.

For example:

- Trending regimes may favour momentum or breakout setups.

- Ranging regimes may suit mean-reversion or bounce systems.

- High-volatility regimes create opportunity but demand wider stops and quicker management.

Investing time considering the underlying market regime may help avoid the temptation to force a trending system into a sideways market.

Simply looking at the slope of a 50-period moving average or the width of a Bollinger Band can suggest what type of market is currently in play.

Sentiment Alignment

If risk sentiment shifts towards a specific (or a group) of related assets, the technical picture is more likely to change to match that.

For example, if the USD index is broadly strengthening as an underlying move, then looking for long trades in EURUSD setups may end up fighting headwinds.

Setting yourself some simple rules can help, as trading against a potential tidal wave of opposite price change in a related asset is not usually a strong foundation on which to base a trading decision.

Key Reference Zones

Context also means the location of the current price relative to levels or previous landmarks.

Some examples include:

- Weekly highs/lows

- Prior session ranges, e.g. the Asian high and low as we move into the European session

- Major “round” psychological numbers (e.g., 1.10, 1000)

A long trading setup into these areas of market importance may result in an overhead resistance, or a short trade into a potential area of support may reduce the probability of a continuation of that price move before the trade even starts.

Market Structure

Structure is the visual rhythm of price that you may see on the chart. It involves the sequences of trader impulses and corrections that end up defining the overall direction and the likelihood of continuation:

- Uptrend: Higher highs (HH) and higher lows (HL)

- Downtrend: Lower highs (LH) and lower lows (LL)

- Transition: Break in structure often followed by a retest of previous levels.

A pullback in an uptrend followed by renewed buying pressure over a previous price swing high point may well constitute a higher-probability buy than a random candle pattern in the middle of nowhere.

Compression and Expansion

Markets move through cycles of energy build-up and release. It is a reflection of the repositioning of asset holdings, subtle institutional accumulation, or a response to new information, and may all result in different, albeit temporary, broad price scenarios.

- Compression: Evidenced by a tightening range, declining ATR, smaller candles, and so suggesting a period of indecision or exhaustion of a previous price move,

- Expansion: Evidenced by a sudden breakout, larger candle bodies, and a volume spike, is suggestive of a move that is now underway.

A breakout that clears a liquidity zone often runs further, as ‘trapped’ traders may further fuel the move as they scramble to reposition.

A setup aligned with such liquidity flows may carry a higher probability than one trading directly into it.

Confluence

Confluence is the art of layering independent evidence to create a whole story. Think of it as a type of “market forensics” — each piece of confirmation evidence may offer a “better hand’ or further positive alignment for your idea.

There are three noteworthy types of confluence:

- Technical Confluence – Multiple technical tools agree with your trading idea:

- Moving average alignment (e.g., 20 EMA above 50 EMA) for a long trade

- A Fibonacci retracement level is lining up with a previously identified support level.

- Momentum is increasing on indicators such as the MACD.

- Multi-Timeframe Confluence – Where a lower timeframe setup is consistent with a higher timeframe trend. If you have alignment of breakout evidence across multiple timeframes, any move will often be strengthened by different traders trading on different timeframes, all jumping into new trades together.

3. Volume Confluence – Any directional move, if supported by increasing volume, suggests higher levels of market participation. Whereas falling volume may be indicative of a lesser market enthusiasm for a particular price move.

Confluence is not about clutter on your chart. Adding indicators, e.g., three oscillators showing the same thing, may make your chart look like a work of art, but it offers little to your trading decision-making and may dilute action clarity.

Think of it this way: Confluence comes from having different dimensions of evidence and seeing them align. Price, time, momentum, and participation (which is evidenced by volume) can all contribute.

Timing & Execution

An alignment in context and structure can still fail to produce a desired outcome if your timing is not as it should be. Execution is where higher probability traders may separate themselves from hopeful ones.

Entry Timing

- Confirmation: Wait for the candle to close beyond the structure or level. Avoid the temptation to try to jump in early on a premature breakout wick before the candle is mature.

- Retests: If the price has retested and respected a breakout level, it may filter out some false breaks that we will often see.

- Then act: Be patient for the setup to complete. Talking yourself out of a trade for the sake of just one more candle” confirmation may, over time, erode potential as you are repeatedly late into trades.

Session & Liquidity Windows

Markets breathe differently throughout the day as one session rolls into another. Each session's characteristics may suit different strategies.

For example:

- London Open: Often has a volatility surge; Range breaks may work well.

- New York Overlap: Often, we will see some continuation or reversal of morning trends.

- Asian Session: A quieter session where mean-reversion or range trading approaches may do well

Trade Management

Managing the position well after entry can turn probability into realised profit, or if mismanaged, can result in losses compounding or giving back unrealised profit to the market.

Pre-defined Invalidation

Asking yourself before entry: “What would the market have to do to prove me wrong?” could be an approach worth trying.

This facilitates stops to be placed logically rather than emotionally. If a trade idea moves against your original thinking, based on a change to a state of unalignment, then considering exit would seem logical.

Scaling & Partial Exits

High-probability trade entries will still benefit from dynamic exit approaches that may involve partial position closes and adaptive trailing of your initial stop.

Trader Psychology

One of the most important and overlooked components of a higher-probability setup is you.

It is you who makes the choices to adopt these practices, and you who must battle the common trading “demons” of fear, impatience, and distorted expectation.

Let's be real, higher-probability trades are less common than many may lead you to believe.

Many traders destroy their potential to develop any trading edge by taking frequent low-probability setups out of a desire to be “in the market.”

It can take strength to be inactive for periods of time and exercise that patience for every box to be ticked in your plan before acting.

Measure “You” performance

Each trade you take becomes data and can provide invaluable feedback. You can only make a judgment of a planned strategy if you have followed it to the letter.

Discipline in execution can be your greatest ally or enemy in determining whether you ultimately achieve positive trading outcomes.

Bringing It All Together – The Setup Blueprint

Final Thoughts

Higher-probability setups are not found but are constructed methodically.

A trader who understands the “higher-probability anatomy” is less likely to chase trades or feel the need to always be in the market. They will see merit in ticking all the right boxes and then taking decisive action when it is time to do so.

It is now up to you to review what you have in place now, identify gaps that may exist, and commit to taking action!

Introduction The VIX Index, or Volatility Index, often referred to as the "fear gauge," measures expected future volatility in the U.S. stock market. Although it's worth noting that there are VIX variations for gold, oil, and global indices, when people discuss the VIX, they usually refer to the instrument based on the implied (forward looking rather than historical) volatility of S&P 500 index options. Broadly speaking, the VIX is widely used as an indicator of market sentiment and can signal increasing or decreasing risk depending on its direction.

This article aims to clarify how the VIX Index can inform traders about market conditions and discusses ways you can trade this instrument. What Does the VIX Index Tell Us? Measure of Volatility: The VIX calculates the market's expectations for volatility over the next 30 days.

Higher VIX values indicate higher expected volatility, while lower values may be suggestive more potential stability. Market Sentiment Indicator: Many investors view the VIX as a barometer of investor sentiment, particularly those of fear, or complacency.A rising VIX can signal increasing fear or uncertainty in the market often associated with adverse economic conditions, data or significant global events, while a falling VIX may indicate complacency or confidence that good or better times after a market shock may be likely.Such movements may be short or longer term in nature dependent of course on the underlying cause of such potential sentiment changes and the perceived longevity of related events and their implications. Non-Directional: Although theoretically the VIX doesn't necessarily correlate with market direction, its true essence is one of an indication about the expected magnitude of price movements, whether up or down.Times of uncertainty, actual or potential, can influence the likelihood of prices moving away from their current positions, thereby increasing volatility.However, it's worth emphasizing that such uncertainty is usually negative in connotation rather than positive.

This is why we often see an inverse relationship between the VIX and the S&P 500. The Inverse Relationship with the S&P500? The S&P 500 Index and the VIX Index are often described as inversely correlated.

However, it's crucial to understand the nuances and exceptions to this relationship. Generally speaking, during periods of high uncertainty or market stress, investors may use options to hedge against potential losses in their stock portfolios, driving up implied volatility, and thus the VIX. Conversely, when investors are confident, stock prices tend to rise and volatility decreases, invariably causing the VIX to drop.

Potential Exceptions and price considerations Short-term Deviations: There can be short-term periods where both the VIX and the S&P 500 move in the same direction. For instance, in a strongly trending bullish market, traders might buy calls (upside options) to leverage their gains, driving up implied volatility and the VIX along with the market. Degree of Movement: The inverse relationship doesn't necessarily imply a 1-to-1 movement (or even a defined multiple of) irrespective of the direction.

As an example, the S&P 500 might drop by 1%, but the VIX could surge by as much as 10% or more.Technical analysis may have a part to play in the degree of movement in both instruments as well as any level of continued uncertainty and implications of this going forward Volatility "Clustering": High volatility periods often cluster, meaning that a single significant drop in the S&P 500 might result in a prolonged period of high VIX values and an apparent “slowness” to drop again, even if the market actually starts recovering or appears increasingly likely it may do so. The reason for this is unclear, but logically after a significant market shock there may be prolonged period of market sensitivity before investors are prepared to believe that any ensuing recovery is sustainable. Practical Applications for Traders and Investors It is worthwhile briefly outlining the motivations and approaches as to why someone may consider trading outside that of a pure directional play.

Hedging: When the S&P 500 is doing well but the VIX starts to rise, it might be a warning sign of increasing uncertainty. Investors may choose to hedge their portfolios by buying VIX options or futures/CFDs. Market Timing: Some traders use the VIX for market timing.

For instance, an extremely high VIX value might indicate a market bottom, while a very low VIX value could suggest a market top. Pairs Trading: Sophisticated traders sometimes engage in pairs trading, going long on one index while shorting the other, aiming to profit from the reversion to the mean of the correlation between the two. How Can You Trade the VIX?

VIX Futures and Options: These derivatives allow traders to take positions based on their expectations for future changes in volatility. CFDs (contract for difference) based on the VIX futures contracts are also available om many trading platforms as an alternative. Exchange-Traded Products (ETPs): ETPs like VIX ETFs and ETNs provide a more accessible way for individual investors to gain exposure to volatility.

Again these may be available of some MT5 platforms such as the one offer through GO Marekts, who provide access to US share CFDs including ETFs. Pairs Trading with S&P 500: Traders may also consider strategies that involve trading the VIX in conjunction with the S&P 500.Tihs should be consider an approach for experienced traders only with clear strategies to action both entry and exit of such positions. Utilize Technical Analysis: Since the VIX is a tradable instrument (whatever the variation in instrument), technical indicators may still be relevant particularly key levels such as support and resistance levels or pivots.

In summary The VIX index serves as an important gauge of market volatility and sentiment and can be useful as a daily "check in" insight of current market state. Trading the VIX presents opportunities but also unique challenges and risks as well as offering some guidance on market state. In terms of trading opportunities it may be suitable for experienced traders with a solid understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

There are a few different ways to actually trade the VIX, commonly for those using MetaTrader platforms such as you would with GO Markets, a CFD is available that is based on the VIX futures contract.

Currency appreciation refers to the increase in value of one currency relative to another currency or basket of currencies. Depreciation refers to the opposite scenario where a currency loses value against another. When a currency appreciates, it takes more units of other currencies to purchase one unit of the appreciating currency, and of course in depreciation the reverse is the case.

These have implications for the economy and, of course, for those who trade Forex. Various influences can impact on this phenomenon and this article briefly outlines some of these factors that influence the appreciation and depreciation of a currency and its implications. Factors Contributing to Currency Appreciation and Depreciation Interest Rates: Higher Interest Rates: If a country's central bank raises interest rates, or if market rates increase, the currency often appreciates because it offers better returns on deposits and other interest-sensitive investments.

This effect may be exaggerated if the rate rise occurs unexpectedly. Of all factors discussed, this is arguably the primary influence. Interest Rate Expectations: Even the expectation of higher interest rates in the future, spurred by hawkish statements from central banks and economists, can lead to currency appreciation.

Conversely, if a dovish central bank stance exists or interest rates decrease, this is likely to result in currency depreciation. Economic Growth Strong economic performance with robust GDP growth can attract foreign investment, leading to increased demand for the currency and, consequently, appreciation. Conversely, currency depreciation is often the result when economic growth falls short of expectations.

Inflation Lower inflation compared to other countries can make a currency more attractive, as it preserves the real value of assets denominated in that currency. Higher inflation can have the opposite effect. However, this must be considered in the context of potential interest rate interventions.

Trade Balance If a country exports more than it imports, thereby demonstrating a trade surplus, there will be higher demand for its currency, leading to appreciation. A trade deficit may result in currency depreciation. Capital Flows Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) can also be influential.

An influx of foreign capital into stocks, bonds, real estate, or businesses can increase demand for a country's currency, and of course vice versa should there be a pulling of such out of markets or businesses. Political Stability and Economic Policy Sustained political stability and responsible fiscal and monetary policies can boost confidence in an economy and its currency, leading to appreciation. The reverse can have a detrimental impact on currency valuation.

Global Events: Changes in Commodity Prices: For countries reliant on specific commodities, a rise in those prices can lead to currency appreciation (e.g., Australia, Canada). Global Economic Conditions: Shifts in global economic sentiment and events in major economies can affect currency values. Other Central Bank Interventions: Central banks may intervene in currency markets by buying their currency on the foreign exchange market to influence its value.

Moreover, central bank interventions such as Quantitative Easing (QE) and Quantitative Tightening (QT) will undoubtedly impact currency value. These potential effects are multifactorial and complex, extending beyond the scope of this article. Impact on Traders, International Investors, and Businesses Understanding currency appreciation and depreciation and its underlying factors is vital for currency traders and investors with international exposure.

It affects: Currency Pairs: The relative value of different currency pairs can shift dramatically due to these factors. Export and Import Businesses: A stronger currency can make exports more expensive and imports cheaper. Investment Returns: The value of foreign investments may be affected by currency movements.

Summary Currency appreciation and depreciation are multifaceted phenomena influenced by both economic fundamentals and market psychology. Understanding these dynamics requires a comprehensive view of the global economic landscape and market conditions, enabling traders, investors, and businesses to seize opportunities and manage risks effectively.

What is a PE Ratio, and Why is It of Interest to Investors? The Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio is a metric that measures a company's current share price relative to its earnings per share (EPS). It's a relatively simple calculation, worked out by dividing the current share price by the Earnings per Share.

Traditionally, it has been used as a potential method as part of fundamental analysis to determine the valuation of a stock at its current price, and by comparing it against other stocks, one can make a judgment as to whether a stock is overvalued or undervalued relative to its earnings. In simple terms, a high P/E ratio might indicate that the stock is overvalued and may be worth avoiding, while a low P/E ratio could suggest undervaluation and hence an opportunity to invest and benefit as the price moves up to a fair value. We have discussed P/E ratios and the influences of this fundamental analysis measure in some detail in another article, “PE Ratios: What They Tell You (and What They Don’t),” which you can find HERE.

However, although this is true to some degree, it is far from the whole story. It is equally true that a low P/E ratio may have causative factors that mean you should avoid the stock rather than jumping in expecting a return to former glory. So, in this article, we take a deeper dive into some low P/E ratio causes that may be “red flags” in your investment decision-making.

For each, we will define what the concern may be that merits further investigation and provide examples to assist in highlighting how this may happen. So, in essence, you will have a checklist to use when considering stocks with low P/E ratios as investments. Declining Industry or Sector: A low P/E may be indicative of an actual or potential gradual reduction in overall demand and growth prospects within a particular industry or sector.

Many reasons for this could include changes in policy, environmental concerns, technology advances, customer preferences, and demographics. Although this decline may be permanent in some cases, there may also be temporary declines due to longer-term supply chain issues or healthcare reasons (the recent COVID pandemic being a prime example where overnight the travel industry was hit hard). The difficulty with the more temporary causes is not only the investor's ability to judge the potential duration of the causative factor but also the subsequent time required for recovery after the event has passed.

The more permanent declines may be currently in progress or likely to happen in the future. With current declines, an obvious example would be the move from traditional print media to digital news platforms. The ability, or even the possibility, of a company to adapt is part of the equation to determine the degree of decline.

Assessing the potential for decline poses the challenge of timing, as it is commonly unknown when there will be a substantial impact. An example of this may be the coal industry's decline due to renewable energy adoption. Poor Quality Earnings: Earnings are clearly part of the P/E ratio calculation.

However, this warrants further exploration, as earnings may be temporarily inflated, giving a misrepresentation of the company's true health. Even a company with an already low P/E that appears to have growth based on the latest earnings, and may look attractive, is worth additional checks. One-time events, accounting changes, or other non-recurring factors may all contribute, at least superficially, to earnings that may be indicative of growth potential.

For example, a company’s earnings may be inflated by a one-time sale of intellectual property or an asset. As this may be reflected more obviously in trailing rather than forward P/E, at a minimum, this should be a starting point for any assessment, but it does reinforce the need to view other broader fundamental analysis metrics. High Debt Levels: High debt levels, appearing to support a company’s ability to operate currently, may restrict future flexibility, the ability to service such debt should interest rates or consumer spending landscapes change, and ultimately jeopardize stability.

Even in a company with a comparatively low P/E and relatively good performance currently, the level of debt should be part of your decision-making process when considering stock positions for the long term. Examples of such could be a real estate company highly leveraged during rising interest rate periods or a consumer discretionary retail chain carrying excessive debt in an economic downturn. Lack of Growth Potential: There may be a situation where a low P/E reflects a decrease in price due to the market's perception of limited opportunities for a company to expand its market share, innovate, or increase revenue due to various internal and external factors.

The level of competition and innovation within a specific sector is a key potential factor in this, with a comparison to industry peers helping the investor to identify discrepancies or unique attributes that may suggest that a low P/E ratio is merited and unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future. Examples of this may include a mature telecom company with limited growth in a saturated market or a software company hindered by strong competition and a lack of innovation. Poor Management or Governance: Poor management can manifest in several ways, with varying degrees of potential damage to the company going forward, resulting in a company’s low P/E ratio reflecting trouble rather than value.

Weak leadership or governance may lead to inefficiency, apparent indecision, or strategic mistakes. This can include decisions leading to legal or regulatory issues that may threaten the company's well-being or result in substantial financial penalties. Warning signs could include: A company with frequent CEO changes, indicating instability.

A corporation's history of failed acquisitions, showing poor decision-making. A car manufacturer recalling models due to dangerous design faults. A pharmaceutical company involved in lawsuits over questionable marketing.

Conclusion: Understanding the warning signs when considering a stock with a low P/E ratio involves an in-depth analysis of various aspects, including earnings quality, financial leverage, growth prospects, product relevance, leadership quality, among many others not included in this article. We have focused on what we consider to be the top 5, and we trust this proves to be a useful starting point. Being adept in interpreting these signs is a vital skill that can help traders mitigate risks and make more informed decisions.

The Non-Farm Payrolls (NFP) is one of the most significant economic events data release of the month and is released on the first Friday by the U.S. Department of Labor. It is a comprehensive snapshot of the current state of US employment, and encompasses the total number of paid employees in the U.S. economy, excluding agricultural, government, private household, and nonprofit organization workers.

Both the numbers that form the report and data trends are of particular interest to central banks, (particularly of course the US Federal reserve), economists, market participants and policy makers, as well as having global interest due to the US position as a leader in the global economy. Key points of the NFP Data: Employment Change: The main figure in the NFP release is the alteration in the total non-farm payrolls compared to the previous month. This statistic indicates whether the U.S. economy is creating or losing jobs.

A positive number signifies job growth, while a negative value indicates job reduction. Unemployment Rate: The report includes the headline unemployment rate expressed as a percentage of the labour force actively seeking employment but unemployed. A lower unemployment rate usually is perceived as being positive for the economy.

Labor Force Participation Rate: This metric gauges the proportion of the working-age population either engaged in employment or actively seeking work. Fluctuations in this rate could signify shifts in people's willingness to partake in the labour market. Average Hourly Earnings: The NFP report includes insights into average hourly earnings, reflecting alterations in wage levels.

Escalating wages might signify robust consumer spending and potential inflationary pressures. Market Impact of NFP: The release of the Non-farm Payrolls data ranks among the most important economic events in the calendar, with often substantial implications in the financial markets across multiple asset classes. The market response to NFP release will be largely dependent on the consensus estimates of each of the numbers (with are theoretically priced into markets to some degree) against the actual numbers released, and how close this is to estimates.

A figure that is wide of the mark compared to expectations is likely to produce a more severe market response. Additionally of course, the current state of the economy may increase the significance and alter the response. For example, in an interest rate sensitive environment, where inflation may be higher than desired, a higher number, suggesting that employment markets are robust may give the green light to the Federal Reserve (the “fed”) to tighten rates, and so the market response will reflect that increased likelihood of Fed action.

Generally speaking, the impact and subsequent response will be felt across all asset classes including the following: Forex Market: Pairs involving the U.S. dollar (USD) frequently experience pronounced movements following the NFP data release. Solid job growth and a lower unemployment rate can bolster the USD, while subpar data might result in USD depreciation. Other risk-on currencies such as the AUD, CAD and NZD may fluctuate significantly dependent on whether the data is viewed positively or otherwise.

Stock Market: Favourable NFP data can elevate investor confidence in the economy's strength potentially leading to stock market optimism. Conversely, weaker than expected NFP figures might raise concerns about economic expansion, potentially triggering stock market selling. Obviously, the degree to which this will be the case may be dependent on the individual sector.

Bond Market: As previously discussed, strong job growth could raise anticipations of forthcoming interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve to counter potential inflation, resulting in lower bond prices and higher yields. Conversely, weak job growth could provoke the opposite outcome. Commodity Market:.

A thriving job market might imply augmented consumer spending, potentially fostering demand for commodities such as copper and oil. Conversely, tepid job growth might be perceived as threatening commodity demand. Additionally, the inverse relationship between the USD and gold is likely to influence precious metals prices as the USD valuation alters.

However, it's essential to recognise that market response to data may often be unpredictable and so to try to pre-empt not only what the data may be, but also the market response to such, should be considered as high risk. Acknowledging that market reactions can be significant, it would seem prudent for traders (particularly those with a short-term approach) to have the date of future NFP releases in your diary, and take steps to account for the increased risks within your trading decision making. GO Markets offer regular LIVE sessions during key data releases from Australia and the US, where we observe the immediate market response as it happens across multiple related asset classes.

Check out our Education Hub for more information.

Quantitative trading, often referred to as quant trading, is a trading strategy that relies on the use of mathematical models, statistical analysis, and data-driven approaches to make trading decisions. Often associated with the creation of specific automated trading systems, terms Expert advisors (EAs) on MetaTrader platforms, it a perceived as a specialist branch of the trading world. This article offers a brief overview of quantitative trading and some of the key processes involved in employing this as a trading approach.

What is Quantitative Trading? In a nutshell, quantitative trading involves the systematic application of algorithms and quantitative techniques. These algorithms are designed to identify patterns, trends, and opportunities in financial markets by analysing historical and real-time data, ultimately providing the required information to execute trades.

Quantitative Trading Process: From Idea to Action There are several steps involved in the quantitative trading system process that must all be actioned prior to the implementation of any such strategy in live markets. Data Analysis: Quantitative traders analyse vast amounts of historical and real-time data, including price movements, trading volume, and other relevant financial metrics. They use this data to develop models and strategies that aim to predict future market movements.

Arguably, the increase in the development of machine learning and AI suggests that this approach may evolve further, although a detailed exploration of this is beyond the scope of this introductory article. Algorithm Development: Quantitative traders design algorithms based on the data analysis stage that implement their trading strategies. These algorithms are programmed to follow predefined rules for entering and exiting trades, managing risk, and making other trading-related decisions.

Strategy Testing: Before deploying their algorithms in real markets, quantitative traders extensively test their strategies using historical data. This process is twofold and involves back-testing, which helps traders evaluate how their strategies would have performed in past market conditions, and forward testing to ensure the validity of any back-test results. Risk Management: Risk management should be part of any strategy, and quantitative trading emphasizes strict risk management.

Traders set parameters to control the size of positions, the maximum acceptable loss per trade, strategies to reduce profit risk (i.e. giving too much back to the market from winning positions), and overall portfolio risk in specific and often adverse market conditions. These parameters help mitigate potential losses which of course is crucial in any trading approach. High-Frequency Trading (HFT): Some quantitative trading strategies are categorised as high-frequency trading.

This is where trades are executed at extremely fast speeds, often in milliseconds. HFT relies on technology infrastructure and low-latency connections to execute a large number of trades in a short time and despite concerns of this as an approach on market pricing seems to be subject to ever-increasing popularity as an approach worth consideration. Additional Potential Challenges Outside of risk management related to quant-driven trades themselves, there are four other critical considerations that must be taken into account and may contribute to the success or failure of a quantitative trading approach.

Data Quality and Consistency: Accurate and consistent data is crucial for quant trading. Discrepancies or errors in data can lead to faulty models and incorrect trading decisions. Overfitting (or Curve Fitting): Developing models that perform well in historical testing but fail to work in real-time trading is a common risk.

Overfitting occurs when models are overly complex and tailored to historical data noise rather than genuine market trends. Market Dynamics: Market conditions can change rapidly, and strategies that work in one type of market may not perform well in another. Adaptability is key to staying successful in different market environments.

Some quantitative models run all the time, riding out the fluctuations associated with different market conditions, while others may have "switches" that turn the model on or off based on specific criteria. Technology Infrastructure: Quantitative trading relies heavily on technology, including fast computers, low-latency connections, and robust trading platforms. Maintaining and updating this infrastructure is essential.

Summary Quantitative trading is frequently employed by institutions and professional traders who have access to advanced, specialist technology and data resources. It allows for systematic and disciplined trading while minimizing emotional biases. As technology develops, its prevalence is likely to increase.

However, it requires expertise in programming, data analysis, ongoing monitoring systems, and a deep understanding of financial markets to be successful.

Averaging down is an investment strategy in which an investor purchases additional shares or other assets at a lower price than their initial purchase price. This strategy is employed when the price of the asset has declined after the investor's initial purchase. Through buying more of the asset at a lower cost, the average cost per unit or share decreases.

Averaging down can be applied to various types of investments, including stocks, bonds, commodities, and cryptocurrencies. This article provides an example of what averaging down may look like and explores some of the considerations that must be taken into account prior to implementing such a strategy. Averaging Down – An Example To illustrate the principle of averaging down, consider the following example.

An investor believes in the long-term potential of an AI company's stock, ABC Tech Pty Ltd, and initially purchases 100 shares at $50 per share, resulting in a total investment of $5,000. However, over the next few months, the stock price declines due to market volatility and concerns about the company's financial performance. Initial Purchase: Bought 100 shares of ABC Tech Pty Ltd. at $50 per share.

Total investment: $5,000. Breakeven cost: $50 per share Averaging Down actioned After a few months, the stock's price has fallen to $40 per share. The investor believes that the price drop is temporary.

Rather than selling the shares at a loss of $1,000, the investor decides to employ an averaging-down strategy. The investor purchases an additional 100 shares of ABC Tech Pty Ltd at the current price of $40 per share. Here's how the investment looks after the additional purchase: Initial 100 shares at $50 per share: $5,000.

Additional 100 shares at $40 per share: $4,000. Total investment: $9,000 Breakeven cost: $45 per share The Opportunity in Averaging Down With the average cost per share now reduced from $50 to $45, a profit will be realized if the stock's price eventually rebounds and exceeds $45 per share. If the stock price increases to $55 per share, here is the updated financial picture: Initial 100 shares at $50 per share: Original value $5,000, now worth $5,500 — $500 profit.

Additional 100 shares at $40 per share: Original value $4,000, now worth $5,500 — $1,500 profit. Current total value of holdings: $11,000 from an initial investment of $9,000. Total profit: $2,000 Risks of Averaging Down However, if the stock price declines further to $35, the situation would be as follows: Initial 100 shares at $50 per share: Original value $5,000, now worth $3,500 — $1,500 loss.

Additional 100 shares at $40 per share: Original value $4,000, now worth $3,500 — $500 loss. Current total value of holdings: $7,000 from a total investment of $9,000. Total loss: $2,000 So rather than an opportunity realised there is a compounding of the losses.

This can be exaggerated further should additional averaging down purchases be made at the new lower price, which some who use this strategy would subsequently action. What this example aims to illustrate is that despite any potential advantage, merely buying more of an asset because its price has declined doesn't guarantee that the asset's value will eventually recover. Without proper research and analysis, investors might be investing in an asset with poor long-term prospects.

So, the key message is that this strategy should be based on additional considerations that must form part of the decision making. Key Considerations for Averaging Down As we have outlined, averaging down can be a tactical move when executed with careful consideration of the asset's fundamentals and market trends. It can be particularly effective for investors with a long-term perspective who believe in the asset's long-term potential.

However, the following represent some of the considerations that must be at the forefront of any such decision. Potential for Larger Losses: As already referenced but is worth re-iterating, averaging down carries the risk that the asset's price might continue to decline after additional purchases. This can result in larger losses if the price does not recover as anticipated.

The reason for any decline must be fully investigated. Of course, it could be a simple short-term market fluctuation that may be taken advantage of, but it is vital to explore whether there is a more permanent decline in company performance meaning recovery is less likely. Sunk Cost Fallacy: Averaging down can lead to a cognitive bias termed sunk cost fallacy (or sunk cost bias), where investors continue investing in a losing position because they've already committed capital.

This can prevent them from objectively assessing the asset's true potential and an emotion-based refusal to accept that the loss in value may not recover. Loss of Diversification: Overcommitting to an averaging down approach in a single asset can lead to an imbalanced portfolio, reducing diversification and so arguably increasing overall risk. Opportunity Cost: Funds used for averaging down could potentially be invested in other assets with better potential for growth.

Investors need to assess whether averaging down is the best use of their capital and so by committing more into a single asset may be losing opportunities in another. Time Horizon: Averaging down often requires a longer time horizon to potentially realise any potential gains. If an investor needs liquidity in the short term, this strategy might not align with their investment profile or goals.

Psychological Stress: Sustained declines in an asset's price can lead to emotional stress for investors who are hoping for a recovery. Emotional decision-making can lead to poor choices. Using averaging down as a substitute for a clearly defined exit strategy: Any investment should be underpinned with a soldi and unambiguous risk management foundation.

Averaging down is often employed without due consideration of this reality and often employed by those without clearly defined exit points for longer term positions. Summary Averaging down can be useful if applied thoughtfully and with a clear risk management plan. However, it comes with its own set of risks, and investors must carefully consider their risk tolerance, investment goals, and market conditions before deciding to implement this strategy.

As always, it's crucial to maintain a well thought out portfolio, conduct thorough research, and avoid emotional decision-making.