New U.S. Sanctions on Russia as Putin Conducts Nuclear Tests

The U.S. has imposed new sanctions on Russia's two largest oil companies, Rosneft and Lukoil, after planned peace talks between Trump and Putin collapsed on Wednesday.

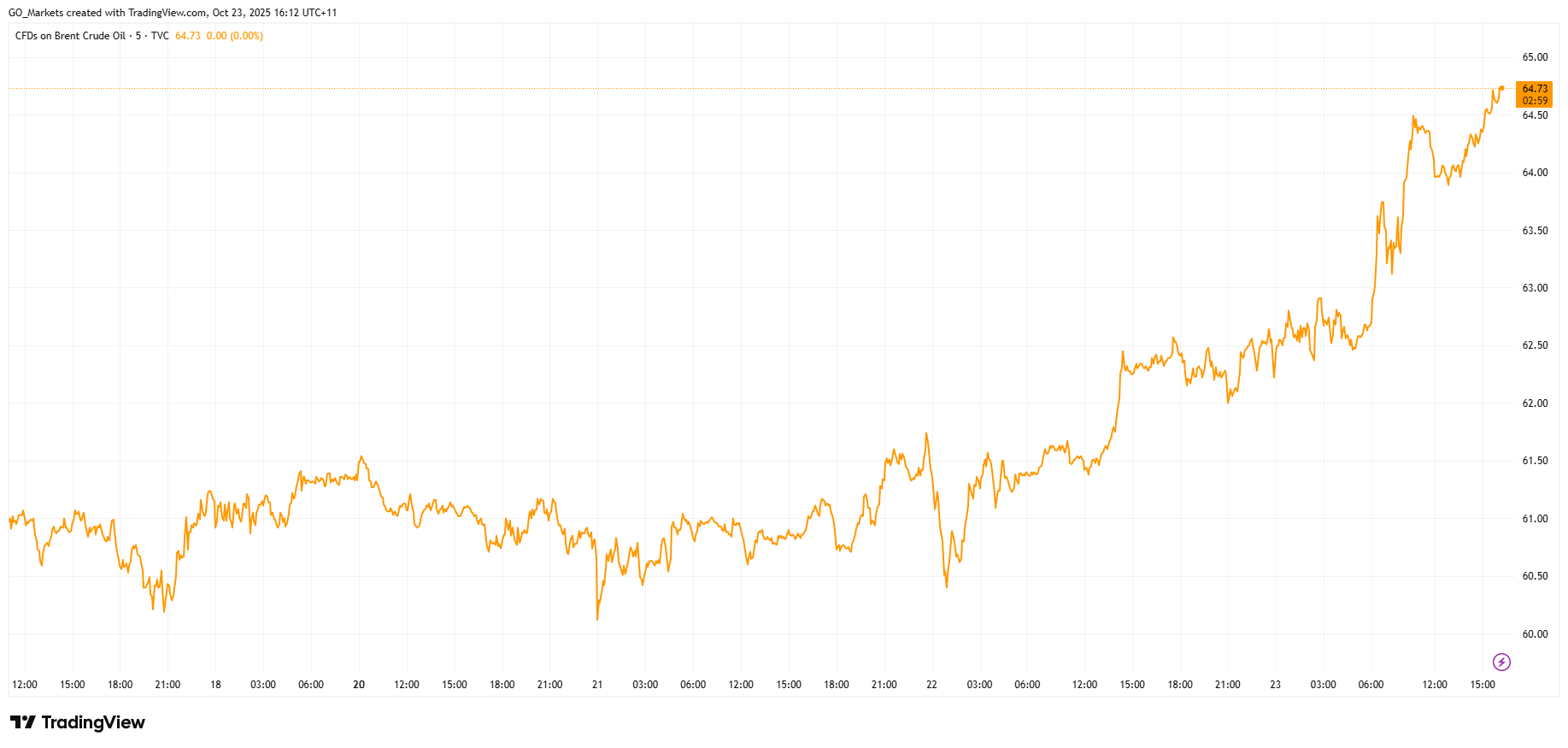

Oil prices spiked 3% after the announcement, with Brent crude hitting $64 per barrel.

The targeted companies are among the world's largest energy exporters, collectively shipping about three million barrels of oil daily and accounting for nearly half of Russian production.

The sanctions build on recent European measures, as the UK targeted the same companies last week and the EU approved its own sanctions package on Wednesday.

In a show of force coinciding with the new sanctions, Putin supervised strategic nuclear exercises on Wednesday involving intercontinental ballistic missile launches from land and submarine platforms.

While the Kremlin emphasised these were routine drills, the highly coincidental timing is notable.

For markets, the key question now is whether secondary sanctions will follow, and if Trump’s enforcement remains strict. Traders will watch closely for any TACO signals that see Trump ease pressure in an attempt to restart negotiations.

Historic PM Wasting No Time on Celebrations

Sanae Takaichi made history this week as Japan's first female Prime Minister. The 64-year-old conservative leader, dubbed the "Iron Lady,” is already rolling out an aggressive policy agenda that could reshape Japan's economic and geopolitical position.

Her first major move is an economic stimulus package expected to exceed US $92 billion. The package includes abolishing the provisional gasoline tax and raising the tax-free income threshold from ¥1.03 million ($6,800), moves designed to put more money in consumers' pockets and battle inflation.

Her next move will come when Trump arrives in Tokyo next week, as the Japanese government is finalising a purchase package including Ford F-150 pickup trucks, US soybeans, and liquefied natural gas as sweeteners for trade talks.

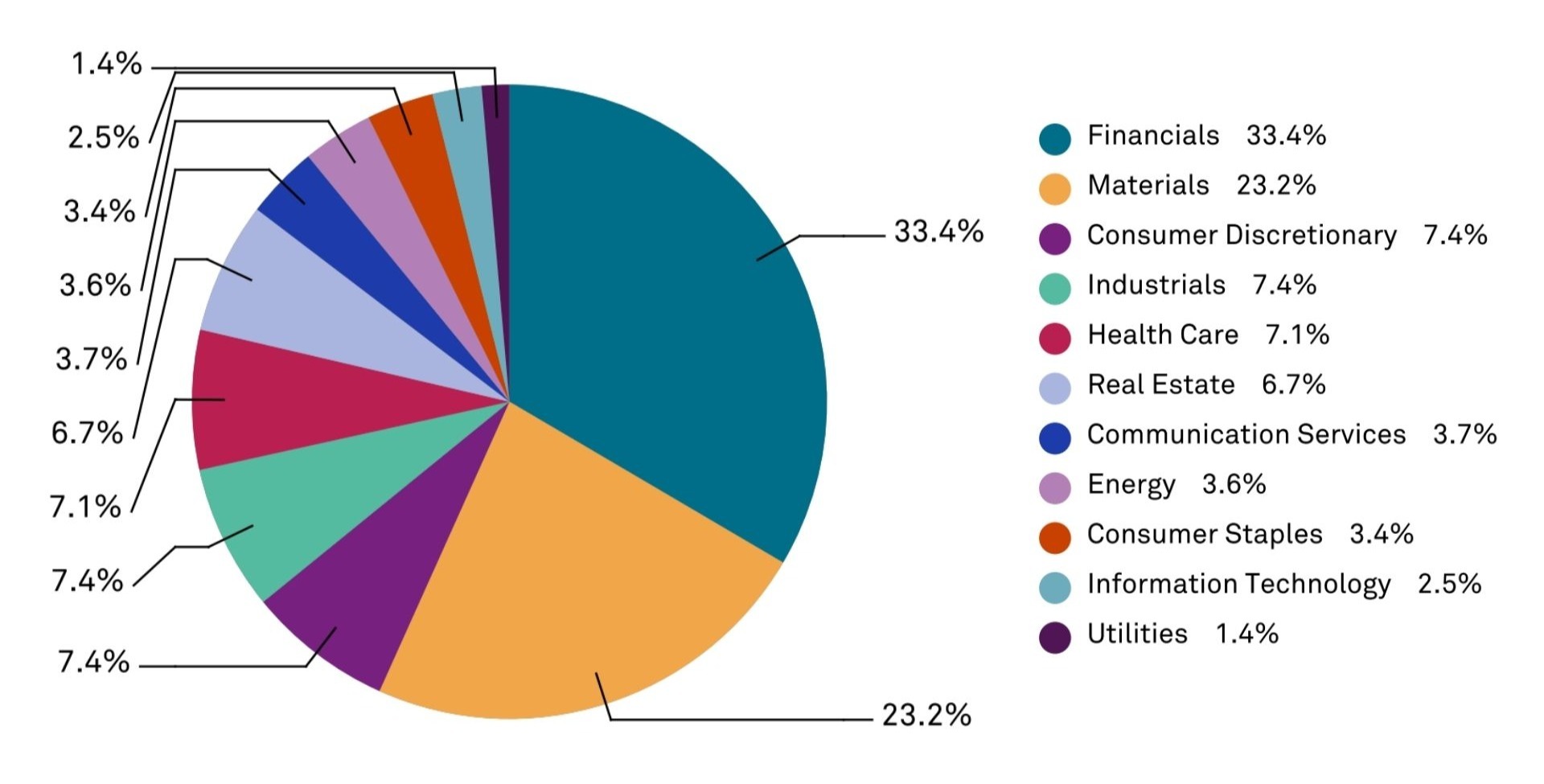

Takaichi has campaigned on being a champion for expansionary fiscal policy, monetary easing, and heavy government investment in strategic sectors, including AI, semiconductors, biotechnology, and defence.

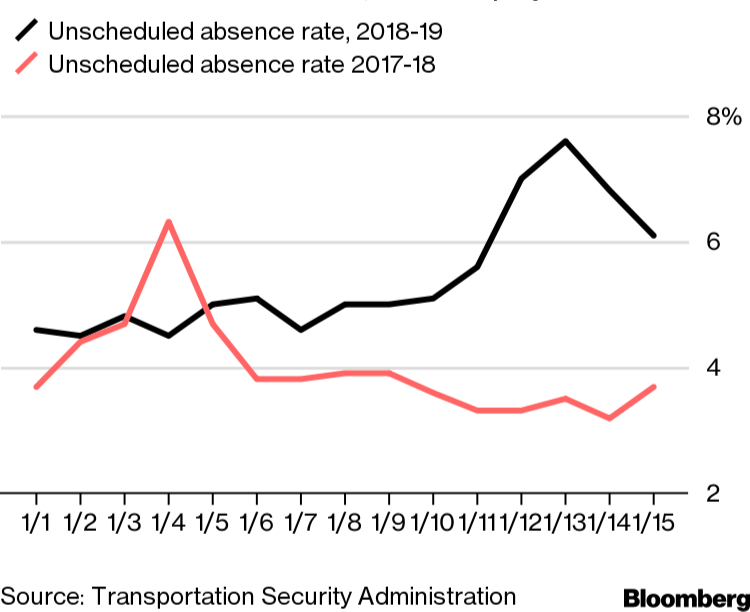

Critical Workers to Miss First Paycheck Due to Shutdown

The U.S. government shutdown is on the verge of creating a crisis for aviation safety, with 60,000 workers set to miss their first full paycheck this week.

These essential workers, who earn an average of $40,000 annually, already saw shortened paychecks last week. By Thursday, many will receive pay stubs showing zero compensation for the coming period, forcing impossible choices between basic necessities and reporting to work.

During the last extended shutdown, TSA sick-call rates tripled by Day 31, causing major delays at checkpoints and reduced air traffic in major hubs like New York — disruptions which are directly attributed to pressuring the end of the previous shutdown.

The National Air Traffic Controllers Association warns that similar pressures are building, with many workers soon to be facing a decision between attending their shift or putting food on the table.

.jpg)