Estratégias de negociação para embasar sua tomada de decisão

Explore técnicas práticas para ajudar você a planejar, analisar e aprimorar suas operações.

A volatilidade tem um jeito de aparecer sem ser convidada.

Um dia, o ASX está flutuando silenciosamente... e no outro, os requisitos de margem aumentam, as paradas não são preenchidas onde o esperado e os portfólios abrem com lacunas desconfortáveis da noite para o dia.

Se você está procurando por respostas, não está sozinho. Algumas das perguntas mais pesquisadas sobre volatilidade entre os negociadores australianos estão relacionadas a chamadas de margem, derrapagens, lacunas noturnas, fundos negociados em bolsa (ETFs) alavancados e ferramentas como o Average True Range (ATR).

Aqui está o que está acontecendo.

Por que isso importa agora

Os mercados globais se tornaram mais sensíveis às taxas de juros, dados de inflação, geopolítica e fluxos impulsionados pela tecnologia. Quando a liquidez diminui e a incerteza aumenta, as oscilações de preços aumentam. Isso é volatilidade.

E a volatilidade não afeta apenas a direção dos preços, ela muda a forma como as negociações são executadas, quanto capital é necessário e como o risco se comporta sob a superfície.

Tradução: A volatilidade não se trata apenas de movimentos maiores, mas sim de movimentos mais rápidos e menor liquidez - é aí que a mecânica da negociação é mais importante.

Quer um estudo de caso de volatilidade do mundo real?

Por que meu corretor aumentou os requisitos de margem?

Uma das perguntas mais pesquisadas sobre volatilidade é por que os requisitos de margem aumentam sem aviso prévio.

Quando os mercados se tornam instáveis, os corretores podem aumentar os requisitos de margem em contratos por diferença (CFDs) e outros produtos alavancados. Grandes oscilações de preço podem aumentar o risco de contas entrarem em patrimônio líquido negativo, portanto, aumentar os requisitos de margem reduz a alavancagem disponível e pode ajudar a gerenciar a exposição em condições extremas.

O que isso pode significar na prática

-Uma chamada de margem pode ocorrer mesmo que o preço não tenha se movido significativamente.

-A alavancagem efetiva pode cair rapidamente.

-As posições podem precisar ser reduzidas em curto prazo.

Os ajustes de margem geralmente são uma resposta à mudança do risco de mercado, não uma decisão aleatória. Em mercados altamente voláteis, é prudente presumir que as configurações de margem podem mudar rapidamente, portanto, muitos negociadores optam por revisar os tamanhos das posições e os buffers disponíveis à luz desse risco.

O que é deslizamento e por que meu batente não preencheu meu preço?

Outro tópico pesquisado com frequência é o deslizamento.

A derrapagem pode ocorrer quando uma ordem de parada é acionada e executada no próximo preço disponível. O resultado pode depender do tipo de pedido, da liquidez do mercado e das lacunas. Em mercados calmos, a diferença pode ser pequena, enquanto em mercados rápidos, os preços podem ultrapassar o nível de parada.

Os drivers comuns incluem

-Principais divulgações econômicas ou de resultados.

- Liquidez escassa.

- Pisos de parada lotados.

- Sessões noturnas.

As ordens de stop-loss geralmente priorizam a execução em vez da certeza do preço e, durante períodos de alta volatilidade, essa distinção se torna importante. Ajustar o tamanho da posição e colocar paradas com referência ao movimento típico de preços pode ser mais eficaz do que simplesmente apertar as paradas em condições instáveis.

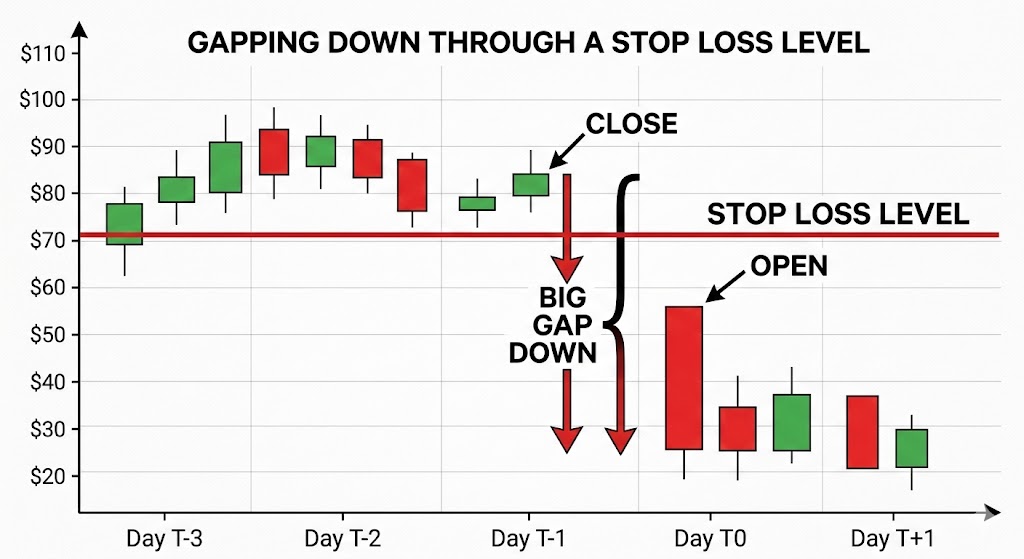

Como faço para gerenciar lacunas noturnas no ASX?

A Austrália negocia enquanto os Estados Unidos dormem e vice-versa. Essa diferença de fuso horário é, infelizmente, uma das razões pelas quais o risco de lacuna noturna é frequentemente pesquisado pelos comerciantes australianos. Se os mercados dos EUA caírem drasticamente, o ASX poderá abrir em baixa na manhã seguinte, sem oportunidade de sair entre o fechamento e a abertura.

Exemplos de abordagens de gerenciamento de risco que os traders do mercado podem usar incluem

-Cobertura de índices usando futuros ASX 200 ou CFDs*.

-Cobertura parcial durante eventos de alto risco.

-Reduzir a exposição antes dos principais anúncios macro.

O hedge pode compensar parte de um movimento, mas introduz um risco básico, pois as ações individuais podem não se mover de acordo com o índice mais amplo.

Não há proteção perfeita, apenas compensações entre custo, complexidade e redução de riscos.

*Os CFDs são instrumentos complexos e apresentam um alto risco de perda de dinheiro devido à alavancagem.

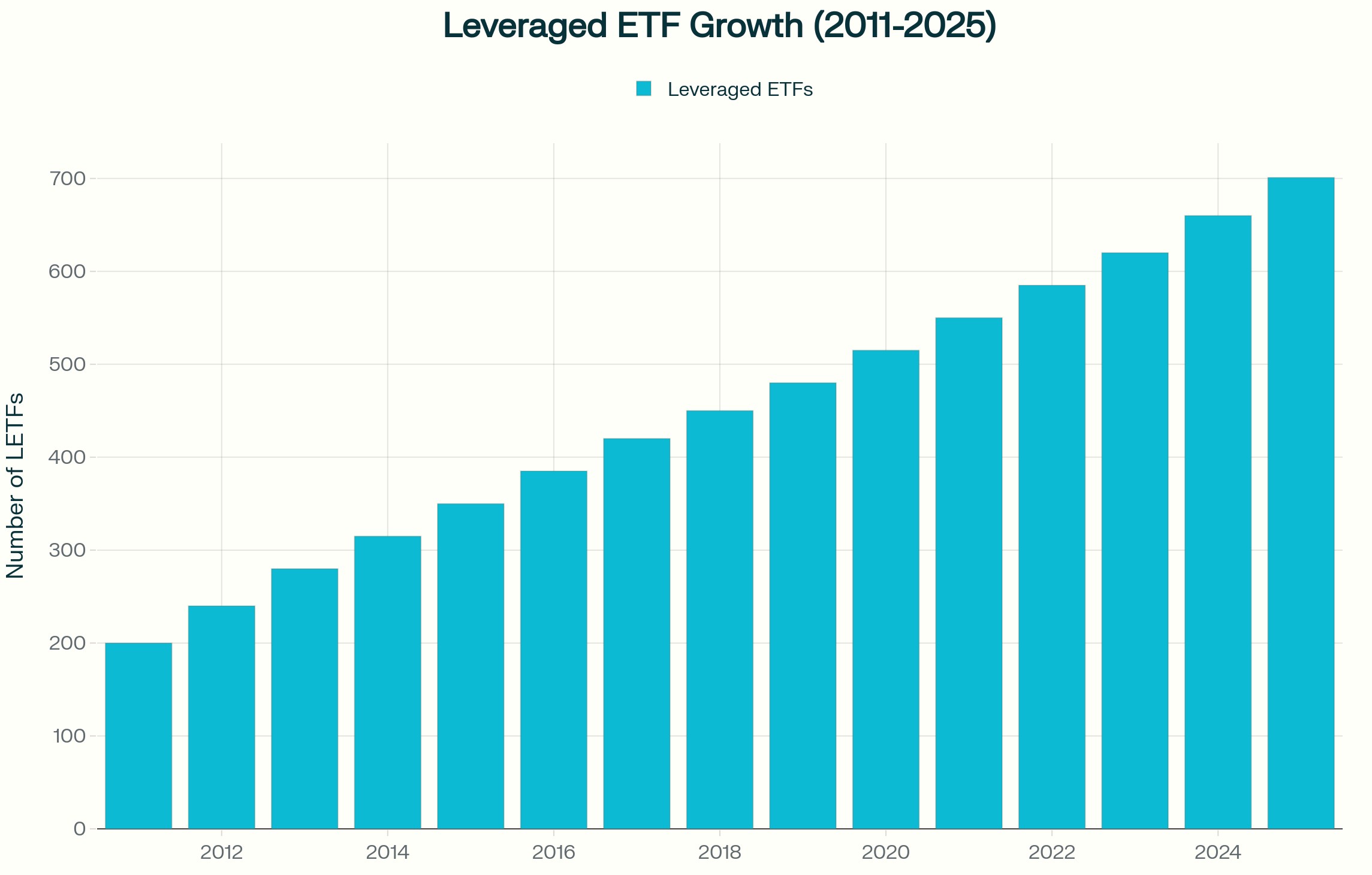

Quais são os principais riscos dos ETFs alavancados ou inversos em mercados voláteis?

Os ETFs alavancados e inversos são frequentemente pesquisados durante períodos de maior volatilidade.

Embora esses produtos normalmente sejam reinicializados diariamente, eles visam gerar um múltiplo do retorno diário do índice, não seu retorno de longo prazo. Em um mercado volátil e lateral, a composição diária pode corroer o valor, mesmo que o índice termine próximo ao nível inicial.

Isso ocorre porque os ganhos e as perdas se acumulam de forma assimétrica. Uma queda de 10 por cento exige um ganho de mais de 10 por cento para se recuperar. Quando esse efeito é multiplicado diariamente, os resultados podem divergir materialmente do índice subjacente ao longo do tempo.

Esses instrumentos podem ser usados taticamente por alguns participantes do mercado. Eles geralmente não são projetados como ferramentas de hedge de longo prazo e entender sua estrutura é essencial antes de usá-los em uma estratégia.

Como o ATR pode ser usado para informar o posicionamento da parada??

O intervalo médio real (ATR) é um indicador comumente usado para medir a volatilidade.

O ATR estima o quanto um ativo normalmente se move em um determinado período, incluindo lacunas. Em vez de definir um stop em uma porcentagem arbitrária, alguns traders fazem referência ao ATR e colocam os stops em um múltiplo, como duas ou três vezes o ATR, para refletir as condições prevalecentes.

Quando a volatilidade aumenta, o ATR se expande e isso pode implicar paradas maiores ou tamanhos de posição menores para que o risco geral permaneça constante. A mudança é deixar de perguntar: “Até onde estou disposto a perder?” a perguntar: “O que é um movimento normal nas condições atuais?”

Considerações práticas em mercados voláteis

Durante períodos de elevada volatilidade, os traders podem considerar

- Permitindo a possibilidade de mudanças de margem

- Dimensionar posições de forma conservadora se a volatilidade aumentar

- Reconhecendo que as ordens de stop-loss não garantem um preço de saída específico

- Analisando a exposição antes de grandes eventos econômicos

- Entendendo a mecânica diária de redefinição de ETFs alavancados

- Usando medidas de volatilidade, como ATR, para informar o posicionamento da parada

- Manter amortecedores de caixa adequados

A volatilidade não recompensa apenas a previsão. A preparação e a conscientização sobre os riscos podem ajudar os negociadores a entender os riscos potenciais, mas os resultados permanecem imprevisíveis.

Leia: Volatilidade global e como negociar CFD

O que isso significa para os comerciantes australianos

Os mercados australianos enfrentam considerações estruturais específicas em comparação com os mercados asiático e americano. O risco de lacuna noturna é influenciado pelo horário de negociação dos EUA e índices pesados de recursos, como o ASX, podem responder rapidamente aos movimentos dos preços das commodities e aos dados da China. A exposição cambial, incluindo movimentos de AUD e dólar americano (USD), pode adicionar outra camada de variabilidade.

A volatilidade não é uniforme entre as regiões. Ele se comporta de maneira diferente dependendo da estrutura do mercado e da profundidade da liquidez.

Perguntas frequentes sobre volatilidade

O que causa picos repentinos na volatilidade do mercado?

Decisões sobre taxas de juros, dados de inflação, desenvolvimentos geopolíticos, surpresas de lucros e restrições de liquidez são gatilhos comuns.

Por que os corretores aumentam a margem em mercados voláteis?

Reduzir a exposição à alavancagem e gerenciar o risco quando as oscilações de preço aumentam.

As ordens de stop-loss podem falhar durante a volatilidade?

Eles podem sofrer derrapagens se os mercados ultrapassarem o nível de parada, o que significa que a execução pode ocorrer a um preço pior do que o esperado. Em mercados rápidos ou ilíquidos, essa diferença pode ser significativa.

Os ETFs alavancados são adequados para cobertura de longo prazo?

Eles geralmente são estruturados para exposição de curto prazo devido a reinicializações diárias. Se eles são apropriados depende de seus objetivos, situação financeira e tolerância ao risco.

Como a volatilidade pode ser medida antes de fazer uma negociação?

Ferramentas como ATR, indicadores de volatilidade implícitos e análise de intervalo histórico podem ajudar a quantificar as condições prevalecentes.

Aviso de risco: períodos de maior volatilidade podem levar a movimentos rápidos de preços, mudanças de margem e execução a preços diferentes dos esperados. Ferramentas de gerenciamento de risco, como ordens de stop-loss e indicadores de volatilidade, podem ajudar na avaliação das condições do mercado, mas não podem eliminar o risco de perda, especialmente ao usar produtos alavancados.

The Relative Strength Index (RSI) is an oscillator type of indicator, designed to illustrate the momentum related to a price movement of a currency pair or CFD. In this brief article we aim to outline what this indictor may tell you about market sentiment, and along with other indicators assist in your decision-making. As with most oscillator type of indicator, the RSI can move between two key points (0-100).

The major aim of the RSI is to gauge whether a particular asset, in our context a forex pair or CFD, is overbought or oversold, and the associated key levels are below 30 (when it is classed as “Oversold”) and above 70 (where it is classed as “overbought”). To bring up an RSI chart on your MT4/5 platform it is simply a case of finding the RSI in your list of indicators in the Navigation box and clicking and dragging it into your chart area. The diagram below illustrates this on a 30-minute chart.

It is generally thought that if the RSI moves into either of these two zones then a change may be imminent. Most commonly the RSI may be used as part of entry decision making. Traders may use this as an additional tick (when other indicators suggest entry) to make sure they do not enter a long trade on an overbought currency pair, or short trade on an oversold currency pair.

Therefore, when articulating this in your trading plan it may read something like the following: a. I will refrain from entry into a long trade if the RSI has moved above 70 on the last trading bar. b. I will refrain from entry into a short trade if the RSI has moved below 30 on the last trading bar.

Less frequently but logically, if one accepts this premise that a move into either of the previous described zones then a trend change may be imminent. It could also be used as a “warning” to potentially exit from an open trade. Traders who wish to explore this in their own trading could: a.

Tighten a trail stop to within a specified number of pips from current price e.g., 10 Pips. or b. Exit the trade entirely. Of course, in either case and with any indicators we discuss, back-testing it with previous trades to ascertain any change in outcomes can be performed to justify a prospective test.

Finally, after gathering a critical mass of trade examples exploring if this would make a difference, this could provide the evidence to suggest whether you should (or should not if there is no difference) formally add to your trading plan. For a live look at how indictors may be used in the reality of trading decision making, why not join our “Inner Circle” group with regular weekly webinars on a range of topic including that of indicators. It would be great to have you as part of the group.

CLICK HERE to enroll for the next inner circle session. This article is written by an external Analyst and is based on his independent analysis. He remains fully responsible for the views expressed as well as any remaining error or omissions.

Trading Forex and Derivatives carries a high level of risk.

Definition of Moving Average In trading, moving averages are often used to smooth out price data to generate trend-following indicators. The most commonly used types are the Simple Moving Average (SMA) and the Exponential Moving Average (EMA). A Simple Moving Average is calculated by defining a period, e.g., 10—or, in other words, the last 10 candles—adding these last 10 close prices, and then dividing by 10.

This is recalculated every time a candle closes and may be plotted as a single line on a price chart. An Exponential Moving Average is often preferred by many traders because it gives more weight to recent prices and appears to be more responsive to price changes than the Simple Moving Average. Ways to Use Moving Averages in Trading Decisions – An Overview Although, like most indicators on a trading platform, a moving average is 'lagging' in terms of the information it provides, its ability to indicate trend direction and changes makes it popular.

For entry points, traders often use two different moving averages, such as a 10 and 20 EMA on a chart. When these crossover so that the 10 is higher than the 20, for example, it may be indicative of a new uptrend (and vice versa for a potential downtrend). Larger moving averages, like the 200 and 50, are commonly observed, particularly when these cross.

For instance, the 50 crossing below the 200 is termed the "death cross" and could indicate a long-term uptrend changing to a downtrend. For exit strategies, rather than waiting for a moving average cross, a more timely exit signal might be a cross between price and a moving average. This is the major focus of this article, and we will discuss this approach along with a few considerations.

Using Price and Moving Average as a Trail Stop So let us first clarify what we mean by a trail stop or trailing stop. Traditionally, a trail stop is a type of stop-loss order that moves with the market price as a trade progresses in your desired direction. For example, if you buy a stock at $100 with an initial stop of $90 and the price moves up to $110, you may "trail" your initial stop from $90 up to $102.

This means that if the trade turns around and moves back down to $102, triggering your trail stop, you would still make a minimum profit of $2 per share, even if the price continues to drop back to $90. If the price doesn't drop but continues to rise, you can move your trail stop higher, for example, to $115, then $120, and so on, until the price eventually falls and triggers an exit. In simple terms, a trail stop locks in profit and manages the risk of giving all potential profit back to the market as the price moves in your desired direction.

Many approaches systematize the use of a trail stop as part of a trading plan, rather than simply using an arbitrary price. One of these approaches is to use a moving average as a trail stop, which we will now discuss in more detail. Moving Average as a Trail Stop Using a moving average as a trail stop means that instead of setting your stop-loss at a fixed dollar amount below the market price, you set it at the level of a particular moving average.

As the moving average changes, your trail stop will move with it. For example, consider the chart below where we have entered a short gold trade on an hourly timeframe at point "A," anticipating a potential trend reversal. The yellow line on the chart is a 10EMA.

The price moves in our desired direction and closes above our yellow line (or the 10 EMA) at point "B," locking in a good profit for this trade. As you can also see, a candle's price crossed temporarily over the 10EMA at point "C" but closed below it. This is an important consideration that we will touch upon later.

Considerations for Traders There are several factors to consider when deciding which approach suits your individual trading style, and these should be tested to find the optimal strategy for you. Which MA Type?: We've already discussed the major differences between Simple and Exponential Moving Averages. Many traders, particularly those trading shorter timeframes, tend to prefer the EMA due to its greater responsiveness to trend changes.

However, just because a particular approach is right for many doesn't mean it can't be different for you. Which Period MA?: This is probably the most debated consideration. A longer EMA, e.g., 20 instead of 10, will require a more significant price drop to trigger, meaning you may give more back to the market if the drop continues.

However, this must be balanced against the possibility that any uptrend may pause and even retrace for a period before resuming its climb. MA Touch or Close?: Another key debate is whether a trail stop using a moving average should be triggered by any touch of that moving average at any time, or whether to wait for a close price through the MA. Both approaches have pros and cons, which need to be weighed carefully.

In Summary There's no doubt that the concept of using a trail stop merits exploration for any trader. Price/MA cross is a relatively easy concept to understand and implement and can improve trading outcomes irrespective of the "fine-tuning" considerations discussed. Your challenge is clear: thorough, ongoing testing is essential to refine your choice and find the optimal method for you.

Strategies Simple Moving Average (SMA) Strategy: Utilizing a 50-day SMA as a trail stop could be effective for longer-term trades. If the price drops below the 50-day SMA, you could trigger a sell order. Exponential Moving Average (EMA) Strategy: For more sensitive, shorter-term trading, a 20-day EMA could be used as a trail stop.

The EMA gives more weight to recent prices and thus responds more quickly to price changes. Price Percentage and MA Combination: You could set a rule where the trail stop triggers if the price drops a certain percentage below the moving average. For example, if the 50-day

Options trading offers a multitude of strategies that cater to various market conditions and risk appetites. One such strategy that traders often employ is the "Long Butterfly Spread." In this article, we will delve into the intricacies of the Long Butterfly Spread, exploring its components, mechanics, and potential advantages. At its core, the Long Butterfly Spread is a neutral options strategy that traders utilize when they expect minimal price movement in the underlying asset.

It involves using a combination of long and short call or put options with the same expiration date but different strike prices. This strategy is particularly useful when you anticipate that the underlying asset will remain relatively stable within a specific range. To construct a Long Butterfly Spread, you'll need to execute three transactions with options contracts.

Let's break down the components: Buy Two Options: The first step involves buying two options contracts. These contracts should be of the same type, either both calls or both puts, and share the same expiration date. One of these options should be an "in-the-money" option, while the other should be an "out-of-the-money" option.

Sell One Option: The next step is to sell one options contract, which should be positioned between the two contracts purchased in the previous step. This sold option should have a strike price equidistant from the two bought options and, like them, should also have the same expiration date. Now, let's understand the mechanics of the Long Butterfly Spread and how it can generate profits: Profit Potential: The Long Butterfly Spread is designed to profit from minimal price movement in the underlying asset.

It thrives in a scenario where the underlying asset closes at the strike price of the options involved in the strategy at expiration. In such a case, the trader reaps the maximum profit, which is the difference between the two middle strike prices minus the initial cost of the strategy. Limited Risk: One of the key advantages of the Long Butterfly Spread is its limited risk profile.

The maximum potential loss is capped at the initial cost of establishing the strategy, making it a prudent choice for risk-averse traders. This risk limitation is due to the fact that the trader is simultaneously long and short options, which mitigates the potential for substantial losses. Breakeven Points: In a Long Butterfly Spread, there are two breakeven points.

The first breakeven point is below the lower strike price of the strategy, and the second breakeven point is above the higher strike price. As long as the underlying asset closes within this range at expiration, the trader will either realize a profit or minimize their loss. Implied Volatility Impact: Implied volatility plays a crucial role in the Long Butterfly Spread.

When implied volatility is low, it reduces the cost of the strategy, making it more attractive. Conversely, when implied volatility is high, the strategy's cost increases, potentially affecting the risk-reward ratio. Therefore, traders should carefully assess implied volatility before implementing this strategy.

Time Decay: Time decay, also known as theta decay, can work in favor of the Long Butterfly Spread. As time passes, the value of the options involved in the strategy erodes. This erosion can benefit the trader if the underlying asset remains within the desired range.

However, if the asset moves significantly, it may offset the time decay benefits. Scenario Analysis: Let's consider a practical example to illustrate the Long Butterfly Call Spread. Suppose you are trading Company XYZ's stock, which is currently trading at $100 per share.

You anticipate that the stock will remain stable in the near future and decide to implement a Long Butterfly Call Spread. Buy 1 XYZ $95 Call option for $6 (in-the-money). Sell 2 XYZ $100 Call options for $3 each (at-the-money).

Buy 1 XYZ $105 Call option for $1 (out-of-the-money). The total cost of this strategy is $1 (6 - 3 - 3 + 1). Now, let's examine the potential outcomes: If Company XYZ's stock closes at $100 at expiration, you will achieve the maximum profit of $4.

The $105 call option will expire worthless so you will lose the $1 you paid, the $95 call option will make a net loss of $1 ($6 cost -$5 profit) and two $100 call options will be worth $3 each. If the stock closes below $95 or above $105, the strategy will result in a maximum loss of $1, which is the initial cost. Any closing price between $95 and $105 will yield a profit or loss within this range, depending on the precise closing price.

In conclusion, the Long Butterfly Spread is a versatile options trading strategy that offers limited risk and profit potential in stable market conditions. It is a strategy that requires careful consideration of strike prices, implied volatility, and time decay. Traders should always conduct thorough analysis and risk management before implementing any options strategy, including the Long Butterfly Spread.

When used judiciously, this strategy can be a valuable addition to a trader's toolkit for capitalizing on low-volatility scenarios.

In the intricate realm of financial markets, options trading stands as a dynamic and multifaceted approach to profiting from market dynamics. Among the diverse range of options instruments, the call option emerges as a fundamental tool. In this article, we will delve into the concept of call options, examining their definition, mechanics, and significance in the context of options trading.

A call option fundamentally operates as a financial contract, conferring a valuable right upon the holder. This right, however, is not accompanied by any obligation to purchase a predetermined quantity of an underlying asset at a specific price known as the strike price, within a predetermined timeframe known as the expiration date. This underlying asset can encompass a wide array of financial instruments, including but not limited to stocks, bonds, commodities, or currencies.

The primary attraction of call options stems from their potential for substantial leverage. In contrast to direct ownership of the underlying asset, which necessitates the full market price, obtaining a call option requires the payment of a premium. This premium constitutes only a fraction of the actual asset cost, thereby allowing traders to control a more substantial position size with a relatively modest upfront investment.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that leverage can magnify both gains and losses, underscoring the critical importance of prudent risk management when trading call options. To comprehend the concept of call options fully, one must dissect their key components. At the core of a call option lies several essential elements: Underlying Asset: Call options derive their value from an underlying asset.

This asset could encompass anything from stocks to indices, commodities, or other financial instruments. Strike Price: The strike price serves as the anchor point for a call option. It represents the price at which the call option holder can exercise their right to purchase the underlying asset.

Importantly, the strike price remains constant throughout the option's lifespan. Expiration Date: Every call option carries a predetermined expiration date. Beyond this date, the option becomes void if not exercised.

These options can have varying expiration periods, ranging from a matter of days to several months or even longer. Premium: To acquire a call option, the buyer must pay a premium to the seller, also known as the option writer. The premium serves as the cost of obtaining the right to buy the underlying asset at the strike price.

To illustrate the mechanics of a call option, consider the following example: Suppose an investor believes that XYZ Company's stock, currently trading at $50 per share, will experience an upswing in the next three months. They decide to purchase a call option on XYZ with a strike price of $55 and a premium of $3. This call option grants the investor the right to buy 100 shares of XYZ Company at $55 per share at any point before the option's expiration date, set three months from the present.

Now, let's explore two possible scenarios: Scenario 1 - The Stock Price Rises: Should the price of XYZ Company's stock surge to $60 per share before the option's expiration, the call option holder can opt to exercise their option. This allows them to purchase 100 shares of XYZ at the agreed-upon strike price of $55 per share, despite the current market price of $60. This transaction yields a profit of $5 per share ($60 - $55), minus the initial premium of $3.

The investor ultimately realizes a net gain of $2 per share ($5 - $3), amounting to a total profit of $200 ($2 x 100). Scenario 2 - The Stock Price Stays Below the Strike Price: Conversely, if XYZ Company's stock price remains at or below the $55 strike price, or even declines, the call option holder is under no obligation to exercise the option. In such cases, the option expires worthless, and the maximum loss for the investor is limited to the premium paid, which in this instance amounts to $300 ($3 x 100).

It is essential to note that not all call options are exercised. In fact, many call options expire without being exercised, especially when the underlying asset does not move favorably or when exercising the option would result in a loss exceeding the premium paid. The decision to exercise or not to exercise a call option lies entirely with the option holder, adding a layer of flexibility to this financial instrument.

Call options find utility across a spectrum of investment strategies. Beyond speculative trading, they can serve as effective hedging tools. For instance, an equity investor concerned about a potential market downturn might purchase call options on an index to offset potential losses in their portfolio.

This strategy allows them to profit from the call options if the market experiences an upswing while limiting their losses if it takes a downturn. In conclusion, call options represent a pivotal component of options trading, offering traders and investors a powerful mechanism to capitalize on upward price movements in various assets. By grasping the fundamental elements of call options, including the underlying asset, strike price, expiration date, and premium, individuals can make informed decisions and implement strategies to align with their financial goals.

However, it's imperative to bear in mind that options trading involves inherent risks, necessitating proper education and risk management strategies before venturing into these markets.

The bid-ask spread is the difference between the highest price a buyer is willing to pay for an asset (the bid) and the lowest price a seller is willing to accept to sell it (the ask or offer). This spread is a fundamental element of market liquidity and represents the transaction cost that traders need to consider when entering and exiting positions. For example, if there is a spread of 1 pip between buyers and sellers, this represented the cost of trade taken.

It is worth pointing out at this stage the much is made of the “spread” in comparison between the value that one broker may offer versus another. However, there are far more influential factors that determine the success or otherwise of trading such as determining high probability entries, effective risk management and appropriate profit taking exits. This is particularly the case for retail investors who trade smaller contract sizes, as opposed to institutional traders, who often trade much larger sizes of trade ad so small differences in spread will have more impact.

Nevertheless, some understanding of the bid/ask spread, and how this may alter at various points during the trading day is important. Factors influencing bid-ask spread Although there are more, we have focused on the top eight factors we think are of not only most influential but have trader relevance. Asset Liquidity: A highly liquid market usually has a smaller bid-ask spread.

When there are more market participants interested in trading a specific asset, there are more bids and asks available, which narrows the spread. In essence, the abundance of buyers and sellers in a liquid market reduces the difference between the buying and selling prices. Trading Volume: Similar to liquidity, higher trading volume often leads to a narrower spread.

Increased trading activity means more frequent transactions, which can reduce the spread. Active markets tend to have more competitive pricing due to the large number of transactions taking place. Asset Volatility: Increased volatility usually results in a wider spread.

When an asset's price exhibits rapid and unpredictable movements, market makers and traders face higher risk. To compensate for this risk, they set wider spreads. This is often observed when major economic data or news is released, causing abrupt market movements.

Market Hours: Spreads might be wider during market open and close due to uncertainty and reduced liquidity. This phenomenon is often seen toward the end of market hours and the beginning of new trading sessions. Additionally, some assets may have wider spreads when traded outside their primary market hours, such as futures contracts associated with indexes that are closed during specific times.

Asset Popularity: Well-known assets usually have tighter spreads compared to less popular instruments. For example, in the Forex market, currency pairs are categorised by liquidity. Major pairs like EUR/USD tend to have tighter spreads because they are highly popular among traders.

Exotic pairs, on the other hand, have wider spreads due to their lower trading activity e.g., US Dollar/Polish Zloty (USDPLN) Regulatory Environment: The level of regulation in a market can influence the spread. Forex markets, for instance, are less regulated compared to stock markets with centralized exchanges. This can lead to comparatively wider spreads in forex trading, as there is no central authority to standardize pricing.

Transaction Size: Large orders can impact the spread, making it wider, especially in less liquid markets. When a trader places a substantial order, it can temporarily disrupt the supply and demand balance in the market, causing a wider spread until the order is executed. Technological Factors: Faster trading systems and networks can lead to tighter spreads.

Advanced technology allows for more efficient matching of buyers and sellers, reducing the spread. High-frequency trading and electronic communication networks (ECNs) contribute to this efficiency by facilitating quicker trade executions. Other factors to consider with the bid-ask spread Slippage and Spread: A significant aspect to consider in trading is slippage, which refers to the difference between the expected price of a trade and the actual price at which it is executed.

A wider spread, indicating a larger gap between the bid and ask prices, can increase the risk of slippage. This happens because, in volatile markets or with wider spreads, it becomes more challenging to execute trades at the precise desired price. Traders may experience slippage when their orders are filled at a different, often less favourable, price due to market fluctuations.

Therefore, traders should be acutely aware of the potential impact of spread size on the likelihood and extent of slippage, especially when trading in fast-moving markets. Stop Placement and Spread: As spreads widen, it's crucial to consider their influence on stop-loss orders. Stop-loss orders are designed to limit potential losses by automatically triggering a trade closure when the asset's price reaches a specified level.

However, an increasingly wider spread introduces the possibility that the spread alone could trigger the stop-loss order. This is particularly relevant when the stop level is set close to the current market price or price has moved towards the stop. Traders need to strike a balance between setting stop levels that provide adequate protection and avoiding premature triggering due to spread fluctuations.

Having a good understanding of the typical range of spreads for the assets they are trading can help traders make more informed decisions when placing stop orders to manage risk effectively. Alternative accounts and differing spreads Some brokers offer different types of platforms that may offer tighter than the spread associated with a standard account. Often, there is a small brokerage payable for such accounts and the trader must decide which is the best option for them.

If you are interested in looking at different account types with different spread at GO Markets then drop our support team an email at [email protected] and we would be delighted to walk you through the options that are available to you. Summary Understanding the bid-ask spread is important for traders as it has the potential to affect many aspects of trading including costs, strategy, risk management, and perhaps even market interpretation. Although there are significantly more influential factors on your potential trading outcomes than the width of the spread, if treating your trading as a business, which arguably is the right approach to have, then knowing about such factors and their impact would seem prudent.

A rights issue, also known as a “rights offering”, is a method that companies use to raise additional capital from their existing shareholders. It involves offering the right to purchase additional shares of the company's stock at a discounted price while maintaining their proportional ownership in the company. This is how the rights issue process typically works: Announcement: The company announces its intention to conduct a rights issue, often through an exchange announcement.

It may, or may not, involve a temporary trading halt by the exchange prior to the announcement for a specified period of time. The rights issue announcement includes details such as the number of additional shares being offered, the price at which these shares can be purchased (usually at a discount to the current market price), and the ratio of shares offered for each share held. Subscription Period: During a specified subscription period, existing shareholders can decide whether to exercise their rights to purchase the additional shares.

The number of additional shares each shareholder is entitled to purchase is determined based on the ratio specified in the announcement. Discounted Purchase Price: The purchase price for the additional shares is typically lower than the current market price of the company's stock. This discount serves as an incentive for shareholders to participate in the rights issue.

For example, assume you already own 100 shares in Company A. Shares in Company A are currently trading at $25. The company wants to raise money, so it announces a rights issue at $20 a share, with the offer open for 30 days.

It sets a conversion rate of one for five. This means eligible shareholders can buy one additional share for every five shares they currently own. The result is you can buy 20 new equity shares for $400, a discount of $100 on the current market price.

Proportional Ownership: By participating in the rights issue, shareholders can maintain their proportional ownership in the company. If they choose not to participate, their ownership percentage might decrease as the total number of shares outstanding increases. The Rights Issue Discount The discount offered in a rights issue can vary widely depending on various factors, including the company's objectives, current market conditions, and the urgency to raise capital.

There is no standard discount that applies to all rights issues, and the discount offered can vary considerably, ranging potentially from around 10% to 40% below the current market price of the stock. Factors impacting the level of the discount offered include: Company's Financial Situation: If the company urgently needs to raise capital, it may offer a larger discount to incentivize participation. Market Conditions: Prevailing market sentiment and volatility can influence the discount.

In a bearish or uncertain market, a more significant discount might be required to attract investors. Investor Sentiment: If the company is well-regarded and the rights issue is perceived positively, a smaller discount might suffice. Purpose of Raising Capital: The reason behind the capital raise (e.g., funding an exciting growth opportunity versus covering debt) can impact investor interest and, therefore, the required discount.

Size of the Issue: The number of shares being issued can affect the discount. A larger issue might require a bigger discount to ensure full subscription. Regulatory Considerations: In some jurisdictions, regulations might set guidelines or limitations on the discount that can be offered.

Recent examples of ASX rights issues Rights issues are common. Here are a few examples from 2022 including the discount offered and purpose. Atlas Arteria Group (ASX: ALX) conducted a 1 for 1.95 non-renounceable rights offer to raise $3,098 million to fund its acquisition of a 66.67% interest in the Chicago Skyway toll road.

Domain Holdings Australia Ltd (ASX: DHG) conducted a 1-for-12.33 non-renounceable rights offer to raise $180 million needed to acquire Realbase Pty Ltd, a real estate campaign management technology platform. Regal Partners Ltd (ASX: RPL) conducted a 1-for-5 non-renounceable rights issue to increase the free float and shareholder base and fast-track the execution of its diversified growth strategy. Healthia Limited (ASX: HLA) conducted a 1-for-12.5 non-renounceable rights issue to provide additional cash reserves to fund near-term acquisition opportunities and provide financial flexibility.

GUD Holdings Limited (ASX: GUD) conducted a 1 for 3.46 non-renounceable rights issue in conjunction with an institutional placement in late 2021, raising $405 million to acquire AutoPacific Group, a designer and manufacturer of automotive and lifestyle accessories. The Market Response to a Rights Issue: The market's view of a rights issue can be influenced by several factors and can vary widely based on individual investor perspectives, market conditions, and the specific details of the rights issue. As part of the announcement and as previously referenced, it is in the company’s interest to effectively communicate the purpose and potential benefits of the rights issue to address investor and market concerns, so creating positive sentiment in an attempt to both support the current share price and encourage participation.

Positive Views: Opportunity to Increase Ownership: Investors who believe in the company's growth prospects might view a rights issue as an opportunity to increase their ownership at a discounted price. This can be seen as a way to acquire more shares at an attractive valuation level. Capital Injection: A rights issue can provide the company with additional capital that it can use to fund expansion, invest in new projects, or reduce debt.

If the market sees these moves as value-enhancing, it could view the rights issue positively. Strengthened Financial Position: If the company uses the proceeds from the rights issue to improve its balance sheet or address liquidity concerns, the market may see it as a positive step toward financial stability. Neutral Views: Dilution Concerns: Existing shareholders might be concerned about potential dilution of their ownership if they choose not to participate in the rights issue.

However, this concern might be mitigated if the discount offered in the rights issue is attractive enough to compensate for the dilution. Market Conditions: The market's overall sentiment and conditions can impact how a rights issue is perceived. In a bullish market, investors might be more willing to participate, while in a bearish market, they might be more cautious.

Negative Views: Sign of Financial Difficulty: In some cases, a rights issue might be interpreted as a sign that the company is facing financial challenges and needs to raise capital urgently. This could lead to concerns about the company's stability and future prospects. Misallocation of Funds: If investors perceive that the proceeds from the rights issue are being misused or not being deployed in a value-accretive manner, it could lead to scepticism about the company's management decisions.

Stock Price Reaction: The announcement of a rights issue can lead to a significant decline in the company's stock price, especially if investors are concerned about potential dilution or question the company's motives. Summary: Participation in a rights issue is a strategic decision that must take into account multiple factors, and there is no one-size-fits-all answer. Shareholders considering participating in a rights issue should evaluate the discount in the context of their understanding of the company's value and prospects, possibly in consultation with a financial professional.